Vasyl Stus couldn’t have acted differently, says Iryna Kalynets

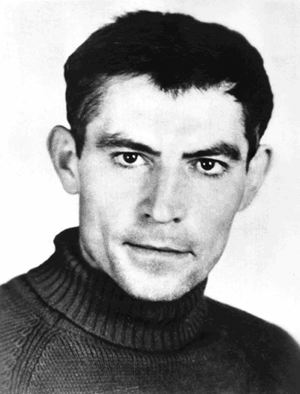

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the death of Vasyl Stus, a brilliant Ukrainian poet and an extraordinary personality, whom Ivan Dziuba described as a “morally crystal-clear man.” He died on the night of September 4, 1985, in a Soviet forced labor camp for political prisoners in the village of Kuchino, Perm oblast (Russia). Iryna Kalynets, a Lviv-based writer, literary critic, prisoner of conscience under the Soviets, shares her memories about Stus, his life, death (and immortality), return to Ukraine, and the understanding (incomprehension) of his human and creative essence by the nation. Stus wrote, “…put your ear to the seashell of memories and listen…”

We don’t die twice.

We live only once

And for all, we live our only life.

Vasyl Stus

Ms. Kalynets, when did you first come across the name and works of Vasyl Stus? When did you meet him?

“I’d known about him before I met him. Poets like Vasyl were never published, but their poems were circulated through samizdat. I remembered his name because Stus’ verse was markedly different from that of other contemporary poets (although there were other interesting poets like Borys Mamaisur and Vasyl Holoborodko, let alone the cult poet, Vasyl Symonenko). Stus stood out from among them with his spontaneous talent, his poems were strikingly memorable; his aesthetic was complemented by a philosophic perception of life and his rejection of what he saw around him. He wrote, ‘I live like an ape amongst the apes…’

“I met Vasyl in 1971, on New Year’s Eve. He was being treated (for ulcers. — Author) at a spa in Morshyn and had visited Lviv. We were singing carols and I actually met him thanks to my little daughter Zvenyslava. She and Vasyl took an instant liking to each other. I saw him tell her something very seriously and she must have been enchanted by his voice, for she was listening intently, looking at him as though she had known him for years. Vasyl took her hand and they walked in my direction. He saw me watching and said, ‘She is a charming young lady.’ I told him she was my daughter. ‘Really?’ he was pleasantly surprised. ‘Yes, and I’m Ihor Kalynets’ wife.’ ‘Is she your mom?’ he asked Zvenyslava and then addressed me, ‘Are you Iryna Kalynets or Iryna Stasiv?’ I told him I was Iryna Stasiv-Kalynets (laughing).

“Then we all strolled down the Lviv streets, I showed him our museums and churches, until I noticed that he was getting very tired. That evening we had a poetic soiree starring Vasyl Stus at our place, on what was Kutuzov and now is General Tarnavsky St. I remember having to act as a hostess while all I wanted was to listen to Vasyl. He recited very nice poems and did it remarkably well. He had a strong stage presence and could masterfully convey every poetic message, with the audience holding their breath, listening to every word. Ihor (i.e., Ihor Kalynets, Iryna Kalynets’ husband, poet and prosaist. — Author) told me later he’d listen to Vasyl day and night, for his poetry was something special. It is true that Vasyl emanated the kind of energy that purified all around him. His wife later told me that everybody was aware of the inner energy coming from that very talented individual, of pure and honest heart.”

Do you remember anything in particular about that tour of Lviv with Vasyl Stus?

“I remember riding to the Yanivsky Cemetery in a streetcar to pay homage to the graves of the Ukrainian Galician Army men. The streetcar was packed and Vasyl guarded me with his hands and kept telling me something, but all I could hear was the magic music of his voice. ‘Are you listening?’ he asked. I said I was, but I was only listening to that music. I also remember visiting the Ethnography Museum and Vasyl saying he’d never had a vyshyvanka (hand-embroidered shirt). He was born in Vinnytsia oblast and lived in Donetsk. No one wore vyshyvankas there.

“On the evening of January 9, Saint Stephanie’s Day, Viacheslav Chornovil and I saw him off to the airport. As the streetcar rode past the KGB building we saw that all windows were lit. I said, ‘There will be arrests soon.’ True enough, 1972 saw many arrests. In fact, they were waiting for Stus in Kyiv (as soon as he returned home they came, searched the place, and arrested him on charges of production and dissemination of anti-Soviet documents and poems; after a long time behind bars, interrogations, forensic psychiatric examination, Vasyl Stus received five years in a maximum security camp and three years in exile. — Author). His term in prison didn’t sever our contact. Vasyl was beside me, on the other side of the fence (Iryna Kalynets and Vasyl Stus served their terms of exile near the village of Barashevo, in Mordovia. — Author) and of course, we found a way to correspond.”

What did Stus write in his letters?

“Above all, he shared information about who had written what, what action was being prepared, and so on; he also asked to pass on messages to our sworn brothers whenever I could; he wrote about books he had read. His moods varied as did his impressions from what he read. Vasyl would share his comments, poems, ideas. He was often ironical. Our correspondence was like a real dialog. I could read between the lines and hear his voice, see his expression, his reaction. Our letters were like those between a brother and a sister, and we really felt that we belonged to the same family. Vasyl would address me ‘My Dear Sister’ and Viacheslav Chornovil wrote ‘My Dear Friend.’”

Were any of his letters nostalgic?

“We were all terribly homesick. While in exile I wrote dozens of letters every day (at long last we could write every other day; in the camp we were allowed two letters a month). Vasyl said I’d missed the opportunity to write letters for too long. He was a man of few words and emotions in daily life; he kept everything to himself and then committed it to paper. Poetry was the ultimate passion with Vasyl. He wrote in a letter that longing for Ukraine forced him to create. In other words, what our torturers thought was our punishment actually gave our life a meaning.”

It gave an impetus to your creativity, didn’t it?

“Yes, it did, it made us work.”

The camp, then exile. What do you remember about Stus at the time?

“I remember Christmas Eve. It was also Vasyl’s birthday, so we, a group of female inmates, decided to sing some Christmas carols for him. Imagine a cold evening and carols echoing through the camp. The next day Vasyl wrote that he’d heard some squealing behind the barbed wire (laughing), and right after that he secretly conveyed (through camp personnel) an excellent poem about carols and maidens’ voices.

“In the summer of 1975 we learned that Vasyl was in a bad physical condition after a brawl provoked by a Russian policeman. He got nervous and his ulcers became worse. We went on a hunger strike immediately, demanding medical aid for Vasyl. Three days later they took him away for treatment.

“In exile Vasyl and I spoke on the phone several times. On one such occasion I made a reservation for a call but got to the telephone exchange two minutes late (my father was visiting me). Vasyl was denied the call, for the first time. I was sorry he had to get up so late (the phone call was scheduled for midnight), considering his poor health. Exile was particularly hard for Vasyl. They made him live in a ‘dorm’ with hardened criminals. They constantly drank, and when they got drunk, they became uncontrollable.

“It was especially sad when they refused to let Vasyl visit his dying father (in August 1978. — Author), although they had to according to regulations. Vasyl went on a hunger strike and called me. I informed Viacheslav Chornovil and Stefania Shabatura immediately. Viacheslav arranged for all political prisoners, in all camps and in exile, to go on a hunger strike in support of Vasyl. I remember composing a letter to Prosecutor General Rudenko, and my closing phrase: ‘Hurry up, Prosecutor General, lest your sons be late coming to your bed.’ I didn’t know that Rudenko was dying at the time… They let Vasyl visit Donetsk to bid a last farewell to his father.

“After exile (Vasyl Stus returned to Kyiv in August 1979. — Author) Vasyl wrote from Kyiv that he was all alone. I knew what he meant — how former acquaintances looked the other way. A world of apes before your very eyes. Vasyl then made up his mind to join the Lviv organization of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. This actually meant another term in a maximum security prison camp (and he got it), constant searches, taking away everything he had written. It was thus that a whole collection of his verse perished, along with his literary translations.

“In his camp notebook he wrote: ‘In Kiev I learned that people close to the Helsinki Group were being repressed in the most flagrant manner. This was the case in the trials of Ovsiienko, Horbal, and Lytvyn, and soon after with Chornovil and Rozumny. I didn’t want that kind of Kiev. Seeing that the Group had been left rudderless, I joined it because I couldn’t do otherwise… When life is taken away, I had no need of pitiful crumbs. Psychologically I understood that the prison gates had already opened for me, and that any day now they would close behind me — for a long time. But what was I supposed to do? Ukrainians were not able to leave the country, and anyway I didn’t particularly want to go beyond those borders since who then, here, in Great Ukraine, would become the voice of indignation and protest? This was my fate, and you don’t choose your fate. You accept it, whatever that fate may be. And when you don’t accept it, it takes you by force.’” (On October 2, 1980, Kyiv City Court sentenced the poet to 10 years in maximum security camps and five years in exile. — Author).

Do you have any mementos of Vasyl Stus?

“Just several letters. You see, there was next to nothing we could take with us when released from the [prison] camp. Vasyl was very frank in his letters, his statements were sharp and to the point. For example, he wrote to explain his joining the [Ukrainian] Helsinki Group and why he had refused to talk to a fellow countryman on KGB payroll simply because he was also Ukrainian — Vasyl hated turncoats from among Ukrainian colleagues the worst, and they hated his straightforward, clearly formulated ideas, his persistence as a poet. I didn’t want the enemy to get hold of these letters, but I kept them. Then one evening (when in exile) I made a pack of them all and tossed it into the stove. Ihor was stunned, but my gut feeling proved right. They broke in early in the morning and searched our place. They were looking for Vasyl’s letters. ‘Where are the letters from Stus?’ [demanded a KGB officer]. ‘Why don’t you dig through our vegetable garden?’ I replied, remembering an old [Odesa Yiddish] joke. They didn’t and I was sorry I hadn’t thought of actually burying the letters there… I have several photos of Vasyl, and his bust. This sculpture belongs to the talented artist, Maria Savkiv-Kachmar. I think it’s Vasyl’s best portrayal; he was like that, always lost in thought, focusing on some idea or other.”

How did you learn about the death of Vasyl Stus?

“About a week before his passing I slept and had a dream about our imminent meeting, then I found myself stepping into his prison cell and seeing no windows, just walls with dirty streaks and patches that looked strange. I asked myself: ‘How could Vasyl possibly live in this narrow space?…’ I realized later that what I’d seen was his coffin.”

In November 1989, you were the coordinator of a project aimed at transferring the remains of Vasyl Stus, Oleksa Tykhy, and Yurii Lytvyn to Kyiv. Dmytro Stus and Oksana, his wife, asked you to do so. Dmytro Stus then arrived to take [the urn with] his father’s ashes. He came with his comrades in arms who wanted the ashes of Tykhy and Lytvyn. What are your most vivid memories about that return to the land of your forefathers?

“The first question I asked when Dmytro was back home was about his reaction when they broke open his father’s coffin. He said, ‘Dad looked the same, except that his skin was darker.’ I was stunned. So many years had passed. And then it dawned on me. Those were the remains a martyr blessed by our Lord.”

A lot has been said and written about Vasyl Stus. The overall impression, however, is that only a handful of individuals are truly aware of his grandeur, of his singular creative talent. Do you think that most of us [fellow Ukrainians] are doomed to misunderstanding and underestimating the Stus phenomenon?

“This depends on the younger generation. Back in the 1960s we found Antonych’s grave in Lviv. It was there we gathered, several young people at a time, to recite his poems, because we realized that one had to read Antonych to communicate with him. The same is true of Vasyl; you have to read his works. Whenever they stage gala shows or other pompous projects in his me-mory, Vasyl Stus isn’t there. Why can’t we honor his memory by organizing small groups of devotees who will recite his poems and pay their sincere tribute to him? Instead, we hear Russian four-letter words and Russian-Ukrainian patois. Is this what our younger Ukrainian generation are all about? If so, how can we discuss our mother tongue, national independence and culture?

“I can’t think of a 20th-century poet matching Vasyl Stus. Probably few are aware of his outstanding creative gift. His verse is a combination of profound philosophical and mystical insight, a remarkable poetic vocabulary, and a striking image-bearing capacity. Many people — among them my students — say that they are emotionally affected when reading or reciting Stus’ poems. Small wonder, because his poems are alive. Back in 1988, we organized a series of Stus poetry soirees in Lviv and every time the audience was packed.

“I don’t think anyone can help the proverbial powers that be overcome their incomprehension of Vasyl Stus. Time passes judgment on everybody, everything. You only live once, but we know that death is only for tangible assets, for the intangible ones are immortal. Try to picture the kind of pressure Taras Shevchenko had to endure, yet his spirit survived, it is with us, here and now. All those truths — culture, national identity, love — pertaining to the national spiritual and cultural heritage cannot vanish because they are the reason behind the existence of man.”

Yevhen Sverstiuk says the winding and thorny path of life chosen by Stus is an exploit.

“I think that people like Vasyl don’t fit into the zealot pattern we know of, they are born that way. They are shown their path and they follow it unwaveringly, for a single step off this road would mean degradation and self-annihilation. Those who say that they are being tortured by their conscience but refuse to atone for their misdeeds realize that they do so out of both their personal experience and that of countless other champions of truth. This boils down to the teachings about love and sacrifice conferred upon us by Jesus Christ. Our Lord now and then blesses humankind with singular individuals who are light at the end of the tunnel, who can help cleanse the whole nation. Otherwise the world would have strangled itself with all that hate and self-annihilation.

“I have repeatedly asked myself how Vasyl would act in the current dirty political situation. I guess he would show an example many of us would be eager to emulate; he would be the first to fight Tabachnyk et al., all those slandering the memories of the Holodomor, campaigning against the Ukrainian language, Ukrainian culture and history. He would defend Volodymyr Shevchenko, rector of Donetsk National University, considering the outrageous manner in which the current Ukrainian government has dealt with him. It is also true, however, that Volodymyr Shevchenko kept a low profile when it came to naming the Donetsk National University after Vasyl Stus. He should have stood his ground [if he had one] the way Vasyl Stus always did.