“The space of freedom” and the continuity of history

April 6 is the 200th birth anniversary of Alexander Herzen, the great Russian thinker, writer, dissident, public figure, the author of My Past and Thoughts. Taking into account that Herzen in no way belongs to the “trendy,” “hyped-up,” and “branded” figures of history, that he often does not fit in with the standard set of pseudo-liberal, pseudo-patriotic, and pseudo-spiritual ideas that prevails in his fatherland, it would be logical to ask why at all The Day is turning to Herzen’s heritage, even on his anniversary day, and, moreover, is inviting Ukraine’s leading and respected intellectuals to take part in this discussion.

We are doing so for the very reason that Herzen embodied the truth and the real freedom of thought (and freedom in general), was an exceptional model of “scattered intellect” (Leo Tolstoy) free of any dogmas, cliches, and the ambitious intention to defend his views not because they hold the truth but because they are “mine.” We are turning to Herzen because he, while loving Russia tenderly and passionately all his lifetime (even though he lived the last 23 years of his life in Berlin, Geneva, Nice, London, or Paris), did not give in, even by an inch, to the “police patriotism of the whip” and “patriotism of the mean and mendacious rabble” (he also used much “stronger” words). We honor Herzen because he defended the freedom of Poland, Ukraine, and all the peoples of the Romanovs’ empire, because Taras Shevchenko had every reason to call him “our apostle,” “our lonely exile” (Diary, the fall of 1857), and the best intellectuals of Ukraine continued this tradition of deep respect for Herzen. After all, we are speaking about this great Russian because his following words are topical today like never before: “I am looking for free people but cannot find any. Then I am crying out: stop! So let us begin with ourselves. Let us create and cherish in ourselves that dreamed-of freedom.”

Among those who reflect on Alexander Herzen, the “reference frame” of his spiritual world, and his contribution to the cause of Ukrainian freedom are Ivan DZIUBA, literature expert, political writer, full member of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences; Myroslav POPOVYCH, director of the Hryhory Skovoroda Institute of Philosophy, member of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences; Mykola ZHULYNSKY, director of the Taras Shevchenko Institute of Literature; Volodymyr PANCHENKO, literature expert, professor at the National University of Kyiv Mohyla Academy; and Serhii HRABOVSKY, political writer, James Mace Prize winner. The roundtable moderator was Larysa IVSHYNA, editor-in-chief of Den/The Day.

In an article contributed to Den on the occasion of Alexander Herzen’s anniversary (see Den No. 58 of April 3, 2012), Oxana Pachlovska recalls a very valuable fact: when there was Herzen’s 100th birth anniversary, Hrushevsky wrote an article which Petliura reviewed on the pages of Ukrainskaya zhizn. A hundred years later, on the occasion of the Russian European-minded thinker’s 200th anniversary, Den invited some leading Ukrainian intellectuals to a roundtable debate on Herzen and Ukrainian freedom.

Larysa IVSHYNA:

“If you recall the Den book project, we asked an extremely important question in the book Dvi Rusi: what can Ukraine do to help Russia? At the time, this looked rather exotic for many because they maintained that Ukraine itself had endless problems. But we took a resolute stand on this matter and history justified us in the long run. Russia, which has serious problems with its own identity, sometimes would not mind ‘grabbing’ a bit of Ukrainian identity. This being a moot point, it is clear that Ukraine will only be able to help Russia if it essentially improves the quality of its intellectual life and ‘comes to terms’ with its past.

“George Shevelov’s article ‘Moscow, Maroseika,’ which we published later last year, became another reason for us not only to think over some of our old internal problems which Shevelov referred to as ‘Little Russia spirit,’ ‘provincialism,’ and ‘Kochubei mentality,’ but also to understand that Moscow, which the article author regards as the then (17th-18th centuries) ‘center of power,’ still remains for Ukraine an essentially ‘internal,’ rather than external, problem which can only be solved, naturally, if serious intellectual efforts are made.

“What kind of Russia do we see today? When interviewed by Radio Liberty’s Russian service, I was reproached for ‘not loving Russia.’ I said it was not true: there are many Russians and many things in Russia which deserve our most sincere affection and respect. I love Russia, but I do not love the empire. I was told in reply that not to love the empire means not to love Russia because it is the same thing. This needs some reflection, doesn’t it?

“I am still convinced that ‘empire’ and ‘Russia’ are not identical notions. There is a tiny fraction of the Russians (it is, of course, a clear minority, a very narrow circle) who adhere to Herzen’s intellectual tradition. We believe in cooperation with them. And this roundtable is an organic continuation of the never-ending Den discussion about the relations between Ukraine, imperial Russia, and democratic, humanistic and really liberal Russia.”

Ivan DZIUBA:

“Speaking of Herzen’s uniqueness in comparison with other Russian and European 19th-century thinkers, I would like to draw your attention to the following.

On the one hand, Herzen was a liberal and democratic critic of any, above all Russian, despotism, but, on the other hand, he was not too happy about the bourgeois world – many things in that-day West European practices irked and outraged him and he commented on them in quite a critical vein.

“Herzen maintained a very difficult relationship with Russian Slavophiles, especially Khomiakov, but, on the other hand, there were also some ‘points of contact.’

Firstly, Herzen showed some ‘class solidarity’ with the Slavophiles, and, secondly, he (as well as the Slavophiles) had certain illusions about Russia being able to ‘leap over’ the bourgeois stage of development owing to the specifics of the Russian ‘commune’ (and even, as Herzen believed, to switch immediately to socialism).”

Myroslav POPOVYCH:

“I would like to broach upon a very important, in the light of today’s events, issue: who is Herzen’s intellectual heir? And have there been any at all? It is the Russian right-wing liberals, including Pyotr Struve, who called themselves ‘Herzen’s heirs.’ In the early 20th century, this was sort of a ‘guideline’ in the propaganda of liberalism. To be more exact, many liberal newspapers and journals of the time wrote about the ‘Herzen-Drahomanov inheritance,’ which is a very telling thing. Drahomanov was a new generation of the national liberal and democratic thought: he read Herzen when he was a schoolboy. What is in common between Herzen and Drahomanov? For Drahomanov was a great Ukrainian patriot. Here lies the fault line between Herzen’s Russian pseudo-heirs, on the one hand, and the heritage of Herzen (Herzen-Drahomanov), on the other. For both Herzen and Drahomanov were utopians as far as visualizing the future of a state is concerned: they opted for a Swiss-type Slavic confederation. But the Russian right-wing liberals, ostensibly Herzen’s ‘heirs,’ mainly favored the idea of ‘Greater Russia.’ This idea could in no way produce the slogan ‘For our and your freedom.’ In this case, we will never see eye to eye with Russian democrats who will be drawing us, one way or another, into the ideology of a great Russian state even if it is a ‘liberal empire,’ as Anatoly Chubais once put it. A national-scale Russian patriotism is unacceptable for us. What can lay the groundwork for our partnership is Russian patriotism based on common human ideals.”

L.I.: “Many are totally unaware of the philosophical heredity of Drahomanov and Herzen. The entire society, especially journalists, is in bad need of this historical ‘crash course.’ Yes, Herzen and Drahomanov may have been utopians at the time, but it is quite possible that a true confederation may serve as a model for today’s Russia.”

HERZEN’S HEIRS: WHERE ARE THEY?

Volodymyr PANCHENKO:

“To see the difference between Herzen and even the ‘most advanced’ Russian democrats of the time, one should look at the following interesting detail. 1863. The Polish uprising has been suppressed. At a Warsaw banquet in honor of this ‘glorious victory of the Russian arms,’ the celebrated revolutionary poet Nikolai Nekrasov recited a laudatory ode to General Muravyov ‘The Hanger,’ the butcher of the uprising. At the same time, Herzen wrote with outrage and contempt about the ‘patriotic syphilis’ that had spread across almost the whole Russia. In other words, Herzen had a rare and very valuable skill to understand others (the Polish in this case).

“Since when had Herzen been taking this attitude? Perhaps since the time when the 22-year-old Alexander, recently a Moscow University student, was implicated in the case of ‘singing pasquinading songs’ (free thinking!) and banished to Vyatka, where he mixed with Polish exiles.

“What was Herzen’s vision of Russia? He once said these well-known wonderful words: ‘We are for a free Poland because we are for Russia, because both of our peoples are shackled with the same chain.’ Oddly enough, this reminds me of the well-known phrase Boris Yeltsin said in 1990-91 to republican leaders: ‘Take as much sovereignty as you can.’ What is the similarity? Herzen made his call in order ruin the ‘Carthage of imperial despotism, while Yeltsin did so to destroy the communist Carthage. Yet history went an entirely different way.

“And in general, when you begin to guess who can be called Herzen’s heirs in the present-day Russian political or intellectual milieu, you gain a not-so-comfortable impression. Maybe, Sakharov, Afanasiev, a few more names… But they are all isolated, lonely figures.”

I.D.: “And please note this: what publications on Herzen have come out in Russia over the past 20 years? There have in fact been no serious studies – just a few small-circulation editions of his fiction (surely, not My Past and Thoughts) in the School Library series. I think it is quite an eloquent fact.” [Here is a good piece of news: Kyivites can get a fresh edition of a book on Herzen by Irena Zhelvakova in the famous series ‘The Life of Outstanding People.’ – Ed.]

L.I.: “With due account of what Mr. Dziuba and Mr. Panchenko said, it is all the more necessary to put into practice these words of Herzen: ‘Let me be a free man, give me ‘a space of freedom.’ It is very important that his ideas be of need in our society.”

V.P.: “Unfortunately, Herzen is not adequately needed today. Apart from Russia, Ukraine, too, should take more interest in him. Mr. Dziuba once said in public that Ukraine ought to have something like an institute of Russian studies.”

L.I.: “Soon after the well-known events in Lviv on May 9 last year, I spoke at the Lviv Polytechnic and also expressed this opinion (to tell the truth, this failed to arouse interest among the audience). Maybe, Lviv would be the best place for an institute of Russia, which would study that country, help understand its complexity, and explore the intellectual tradition initiated by Chaadayev and Herzen. It still seems to me that this will not occur, not in the least because far from all understand why we need this. We could now apply the words Herzen said after the above-mentioned events in Poland to Ukraine – from 1863 to 2012. Poland managed to succeed. It reunited with the European home, while Ukraine is still struggling. And, from this angle, Herzen is, to a large extent, our ally.”

M.P.: “I have long been trying to find out why Herzen’s heritage – a streamlined system of journals, newspapers, and letters – disappeared. That was a structure that somewhat resembles Den which goes off the limits of what is just called ‘newspaper.’ Herzen also had a ‘free press’ structure which disappeared after 1863. One of the versions is that it perished because Russian society, including those who strove for freedom, turned its back on Herzen, when he openly supported the Polish. This is not the evidence of Russia being vicious deep inside. This is a major drama, even a tragedy, of the Russian liberation movement which failed to properly understand what freedom is. Everybody had its own idea of freedom. It is our generation that was supposed to settle these differences, but, unfortunately, we have failed to do this so far.”

1863 WAS A DECISIVE YEAR FOR THE RUSSIAN DEMOCRATIC THOUGHT

Mykola ZHULYNSKY:

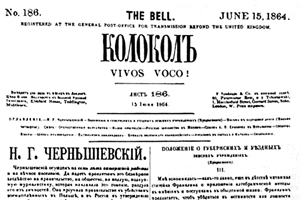

“The first issue of Kolokol comes out in July 1857. In December 1857 Taras Shevchenko arrives in Nizhny Novgorod. He has officially been freed but still has no right to enter the capital. And Shevchenko, who has in fact not written a single poetic line in the past six years, writes the poem Neophytes in Nizhny Novgorod. He is running a grave risk because censors and the government can easily read in the poem that not only Nicholas I was a blood-thirsty tsar (‘a hard-to-forget brake,’ as Shevchenko dubs the tsar in his diary) but that Shevchenko expects nothing good from his successor Alexander II, either. Shevchenko tries to send Neophytes to Mikhail Shchepkin via Panteleimon Kulish. The latter reads the poem and writes back to Shevchenko: ‘Your Neophytes, brother Taras, is a nice thing, but it is better not to print it. You should not remind a good son of his lazy father [Alexander II and Nicholas I, respectively. – Ed.] if you expect the son to do at least some good. He is now the first man here – but for him, we could not take a breath. And the emancipation of serfs is also his merit. It is we, writers, rather than paunchy bureaucrats, who are his kindred spirits. He loves us, he places his faith in us, and faith will not disgrace him. It is not only too early to print this piece – let me, brother, not send it to Shchepkin, for he will be flashing it around, and word will spread that you must not be let into the capital.’

“Another subject: Alexander Herzen writes a letter to Emperor Alexander II, in which he urges him to abolish serfdom, emancipate peasants, and give freedom to the Russian word. After some time he writes the article ‘You have won, Galilean!’ which praises and thanks Alexander II for establishing zemstvo commissions, i.e., laying the groundwork for peasant emancipation. Why am I drawing these parallels?

“It is about a very serious problem which my colleagues have already spoken of. Shevchenko was taking a radical stand and did not believe in a good tsar. Herzen, who opposed Byzantine-style despotism and peasant serfdom, was taking, to a large extent, a liberal attitude. And the 1863 Polish uprising became the turning point in understanding the way which the Russian democratic thought would go. Incidentally, there were very serious problems in the Polish liberation movement, too. The idea was to restore Poland within the borders of 1772, while Herzen spoke about national liberation – he in fact supported the future independence of Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, and Poland, but he spoke of democratization in the sense that he clearly expressed in 1859: ‘I sincerely, from the bottom of my heart, with the Slavic to form a free federation rather than to be torn apart.’ Let us recall here the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood and Mykhailo Drahomanov who was in rapture over Herzen; let us recall the development of these ideas and throw a bridge to Hrushevsky and his idea of a federative union with a democratic Russia. This thread can be drawn as far as the present day.

“One more quotation. Herzen wrote about Ukraine in the article ‘Russia and Poland:’ ‘…untie their hands, untie their tongue, let their language be totally free, and let them say their word then.’ In other words, he defended the right of Ukraine to free speech and independence. But he goes on to say that when Russia ‘enters a new phase of life,’ there will be no reason why Ukraine should break away. This position of Herzen in fact remained unchanged.

“Oddly enough, even these ideas are not very popular among the present-day Russian democrats. All the critical Russian literature, which was full of hatred for despotism, tsarism, and the suppression of freedom and democracy, is not being put on a pedestal in today’s Russia. Why?

“Chaadayev, Gogol… The so-called literature of critical realism in fact laid the groundwork for raising the Russian Raznochintsy (‘people of miscellaneous ranks’) – intellectuals who developed hatred towards and the desire to destroy the exploiters, which they thought needed no adherence to moral principles. But, in this case, Herzen took a noble stand: he was critical of the revolution because he understood that a revolution also implies usurpation, this time by a different force, and there can be no question of a free personality here. And a free individual was an ideal for Herzen.”

L.I.: “The well-known poet Naum Korzhavin, who, incidentally, was born in Kyiv, wrote the following line: ‘You must not rouse anybody in Russia.’ This idealism and noble attitudes of Herzen – and today’s Russia and Ukraine with our idea of freedom… We can even say, with major reservations, that 1863 was a Polish orange revolution of sorts, for it also aroused Russia’s resentment.”

THE FIRST EUROPEAN-STYLE INTELLECTUAL IN RUSSIA

Serhii HRABOVSKY:

“I can remember my impression when I seriously read Herzen well after I had graduated. The impression was: how could THIS have been published in the USSR? For it is subversive literature, scathing criticism of Marx and Marxism, criticism of any form of despotism. He was indeed a critic of capitalism, but we should take into account what kind of capitalism he criticized – it was not a dynamic but a greedy, consumerist, and parasitic rentier capitalism. Herzen’s forte is the rationality and historicism of his thinking (no other Russian thinker had reached this level of rationality ever before). Yes, he thought there would be no reason why Ukraine should break away from a democratic Russia, but, knowing his views, we can assert that if he had seen that he was wrong, he would have admitted his mistake. Herzen did so more than once. It is also one of his best fortes. And, finally, Herzen’s idea of democracy. He said that democracy implied restlessness and something very uncomfortable at times, while it is calmer and more predictable in despotic states – they are full of order, but it is the order of a graveyard.

“In the last years of his activity, Herzen leveled a lot of criticism at revolutions, which break and smash everything around, but when an anti-despotic revolution against Napoleon III began in France, he resolutely supported it. This shows again his rationality, concrete historical thinking, depth, and tremendous erudition. Herzen was in fact Russia’s first European-style intellectual, and I do not think that what he did has gone down the drain. Indeed, Herzen’s attitude to the Polish uprising resulted in a ten-fold drop of Kolokol’s circulation, but there were a few hundred people in Russia who shared this attitude. It is a Russian phenomenon.

“As far as the continuity of Herzen’s line is concerned, we should also mention, in addition to Drahomanov, Narodnaya Volya whose program documents called for dismantling the empire. Naturally, it was Ukrainian influence to a large extent, but the Russians who took part in this movement agreed to the formation of an ‘All-Russian Union’ consisting of seven autonomous states, to the independence of Poland and Finland, etc. In the early 20th century, there were not only the Ukrainians but also some Russians, albeit not in a key poison, in the Party of Constitutional Democrats, who favored the federative setup of a future democratic Russia. In other words, Herzen’s line continued to exist. We can name a large number of Russian litterateurs who worked in this field. But I want to draw your attention – perhaps unexpectedly – to the quite Herzen-style (with all illusions and perturbations) literature of the brothers Strugatsky. It is the serious school of respect for freedom and the individual, which the young people of the entire USSR once went through.

“Herzen’s line is, of course, not mainstream – it is being pushed hard to the background, but it still exists. So it is no mere chance that Russia has been rocked by mass-scale protests in the last six months.

“When Herzen began to publish Kolokol, he spelled out the minimum program: the emancipation of peasants and granting them land, the freedom of speech, and the abolition of corporal punishment, i.e., government’s arbitrary treatment of its subjects. Now, almost one and a half century after the publication of the journal’s first issue, this program in fact still remains topical for both Russia and Ukraine.”

V.P.: “Mr. Hrabovsky, why do you think subversive literature, such as Herzen’s books, was published in the USSR?”

S.H.: “It was a certain ritual. Lenin said the Decembrists had awakened Herzen – so you could not but print his works. I have two volumes of Herzen’s philosophical works published in 1946, the severest Stalinist winter. Of course, his thoughts are ‘trimmed’ there, but if you read it attentively, it will be a serious school of free thought. After all, if you read Karl Marx attentively, you will also see it is subversive literature.”

L.I.: “There’s one more nuance. That Herzen is considered a revolutionary has also played a role, as has the habit of functionaries to take a pure academic approach to texts and decide whether to clear or to ban. For Herzen never openly criticized Lenin or Stalin, while a free thought is something very ephemeral…”

DOES RUSSIA NEED HERZEN?

M.Zh.: “Let me continue about Herzen’s links with Ukraine. Firstly, Kolokol and Poliarnaya zvezda were circulated across the Russian Empire through Ukraine. Secondly, a Kharkiv resident named Bogomolov, who had visited Herzen in London, said on coming back that ‘Iskander [Herzen’s nickname. – Ed.] is pinning a great hope on Little Russia and Kharkiv.’ Thirdly, Kolokol also had its correspondents in the Ukrainian gubernias, who sent 150 articles to be printed. And, finally, Herzen was taking a very respectful attitude to the Zaporozhian Sich, for he viewed it as an ideal democratic republic. The Ukrainian Cossacks’ love of freedom very much appealed to him. This also explains why he so much focused on Ukraine. In one of his articles, ‘On the Development of Revolutionary Ideas in Russia,’ Herzen said: ‘The Ukrainian loves his homeland, his language, and Cossack legends. One century of serfdom could not possibly destroy all that was independent and poetic in this glorious nation.’ We should also remember an article by Mykola Kostomarov, which was printed in Kolokol and made a lasting impression on Herzen.”

V.P.: “Speaking of the Shevchenko touch in Herzen’s life story… In 1857, when Shevchenko stayed in Nizhny Novgorod, he drew a portrait of Herzen with the caption ‘Iskander’ in his diary. Moreover, he did his best to hand over his Kobzar to Herzen in 1860. Herzen’s private library still keeps the Kobzar the poet sent him via Makarov, one of Kolokol’s secret correspondents.

“It is the minority that has always been and will always be following Herzen’s line because, by all accounts, Russia does not need Herzen. I can refer to the authority of Vasily Grossman who said in his novella Everything Flows that Russia and freedom are incompatible things. His arguments essentially boil down to the fact that Russia cannot be a European state because democracy is fatal to her. Once democratic processes begin in Russia, it tends to disintegrate. So Herzen-type people are of no use for Russia. Rather, the latter needs what Herzen called ‘patriotic syphilis.’”

L.I.: “Many processes in Russia are really far from being democratic. But if Russia miraculously became a fully democratic country, what kind of Ukraine would it have to deal with? And it is our headache to raise the bar in our own country.”

Ihor SIUNDIUKOV: “Many well-known Russian people used to come to London to see Herzen in person. I would like to mention two visits. 1862. A year has passed since the death of Taras Shevchenko. Herzen is visited by Count Fyodor Tolstoy’s daughter who played an important role in the liberation of Shevchenko. Naturally, they could not but recall the poet. Herzen said he could compare Shevchenko with Koltsov, for he was also a low-born poet, but, in addition, Shevchenko was of great political importance for his people. It is really surprising that Herzen managed to assess Shevchenko’s historical role so wisely and sagaciously.

“Two years before this, Herzen was visited by Nikolai Chernyshevsky. It is a less known visit which is even veiled in secrecy, but Herzen’s relatives left some reminiscences of it. They recall that there was a heated dispute, in fact a quarrel, between Herzen and Chernyshevsky. A month later, Kolokol received a letter from an unknown Russian. It had just a few, but terrible, words: ‘Call on Rus’ to take the axe!’ Herzen printed this letter in the journal, although he dissociated himself from it and said the journal was not happy about such letters. On his part, Chernyshevsky had radicalized his position and fully approved of this letter. I think it was a turning point in the Russian liberation movement. Herzen’s approach was to categorically reject violence, no matter what exalted goals may be justifying it, whereas the approach to which Chernyshevsky was inclined obviously allowed revolutionary violence.”

V.P.: “I will complement your note with the words of Bakunin: ‘Poison, the knife, the noose – the revolution will justify all this.’ This slogan was unacceptable for Herzen.”

L.I.: “But this very line won in the end…”

I.D.: “It is a difficult and disputable subject. Leo Tolstoy once heatedly polemicized with [Russian Prime Minister] Stolypin about the revolutionaries who were given ‘Stolypin’s neckties’ [i.e., were hanged. – Ed.]. He said: ‘I know many atheists and revolutionaries who are much more moral than all clergymen.’ Likewise, if you read the speeches of some revolutionaries during their trials, you will see a great deal of humanism in them, and even the tsarist judges would give in to them.”

M.Zh.: “The Russian Empire was really going through the mill at the time. For example, there were three attempts on the life of Alexander II who met liberal democrats halfway in many respects and freed peasants from serfdom, and finally he was assassinated by radical revolutionaries whom Chernyshevsky, Dobroliubov, and Belinsky, of course, supported…”

S.H.: “As for Alexander II… I am sorry, but during the ‘peaceful mingling with the people’ in the mid-1870s, thousands of revolution-minded young people were detained and dozens of people were killed in prisons without any investigation or trial. Revolutionary violence was a response to this very lawlessness.”

L.I.: “There are calls for violence, simplification, and radicalism, but there are no calls for improving general education and developing a civil society. Meanwhile, the ideology of simple decisions often produces a tragic result.”

HERZEN CRITICIZED THE BUREAUCRACY AND THE REGIME

M.P.: “Herzen knew very well and liked Andrii (Andrzej) Potebnia. He understood the ‘inner mechanism; of this person who was doomed to a tragic end – he was killed during the 1863 uprising. He went to die because of his inner integrity. This deeply moved Herzen, for he, like Potebnia, had also been in fact doomed to death and died young. We can find a lot of examples like this. Everyday life in Russia used to beget self-sacrificingness which was often unnatural and unjustifiable, amounting to affected feeble-mindedness – a warped soul of sorts. We have not gone too far from Russia.”

M.Zh.: “But we are in a more favorable situation, for we are getting rid of the colonial syndrome, while Russia is trying to assume it.”

Viktoria SKUBA: “Mr. Zhulynsky said in his speech that Herzen had respected and admired Ukrainian Cossacks. But I wonder if Herzen recognized Ukraine’s right to something more than the Cossacks and love of freedom. What did Herzen think about Ukrainian history? Did he accept Ukraine’s right to being the successor of Kyivan Rus’?”

S.H.: “In the times of Herzen, the Ukrainians did not aspire for complete political independence. It was usually about free education, translation of the Gospel… The idea of a pan-Slavic federation, which the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood endorsed, was sort of a maximum. It should have taken a certain time, of course, for the project of an independent and united Ukraine to emerge – at least for being able to study theoretical possibilities and gain practical experience. Let’s face it: even the word ‘Ukrainian’ was not much used at the time. It is no mere chance that the young Lesia Ukrainka wrote to Drahomanov: we are not called Ukrainophiles, we are just called Ukrainians. This confirms the fact that the young intellectual elite finally opted for this word as late as in the times of Lesia Ukrainka. Yet this rarely occurred. For example, Taras Shevchenko did not use the word ‘Ukrainian.’”

M.Zh.: “Shevchenko writes UkrAina…”

S.H.: “Incidentally, Pushkin’s Poltava has Ukraine, not Little Russia. As for Herzen, he wrote, as Pushkin did, ‘in Ukraine’ rather than ‘on Ukraine’ in his works. Coming back to the question, the Herzen-time Ukraine was not mature enough to accept the ideas of independence and self-identification.”

Vadym LUBCHAK: “As for the importance of Herzen for today’s Ukraine, let me quote his words: ‘Even if a Little Russian becomes a noble, he never breaks with his people as fast as a Russian does. He loves his homeland, his language, and stories about Cossacks and hetmans. Ukraine has been aspiring for a wild, belligerent, but also republican and democratic, independence for centuries on end. Drawn into a war, the Ukrainians have never been laying down their arms.’ Today, the Ukrainians seem to be entirely different.”

I.D.: “In one of his works, Herzen asks himself if the Ukrainian will abandon his free melodious language in favor of the mean and bureaucratic language of the empress. Without trying to characterize the two languages now (for it is improper to speak of Russian as only the language of the authorities and the bureaucracy), I must say that, unfortunately, the ‘free Little Russian’ has abandoned his tongue. Many of Herzen’s characteristics are painfully echoing today.

“As for treating Herzen’s works as ‘subversive’ literature, let us not forget that colonialism, even in the Bolshevik variant, always proclaimed itself the heir to humankind’s total humanitarian heritage. Accordingly, many things were published in that era. Such virtues as justice, honesty, and equality were inculcated in us from our schooldays onwards. But whenever a young person embarked on the adult path of life, he or she saw entirely different things. Hence were the morbid processes of double standards and all kinds of misunderstandings. It is one of the sources of dissidence and protest movements in the Soviet Union.

“Are there any grounds to say that Herzen was the first Russian dissident, emigre, and the precursor of 20th-century Ukrainian and Russian dissidents? I don’t think so. He was not the first. I would say the first was Prince Kurbsky who unleashed a war against Ivan the Terrible, when he was in exile. We can also recall a lot of critical publications about Catherine II to whom monuments are being put up now. Her political hypocrisy was being widely exposed even at that time. But Herzen is special in that he refused to make personified and narrow-subject accusations. He would systemically criticize the Russian bureaucracy and the Russian regime. It is the new thing which Herzen brought over and Drahomanov picked up later. Incidentally, about the links of Herzen with Ukraine. In 1865 the legendary Ahapii Honcharenko, a Kyiv priest and revolutionary, arrived in America. He had often visited Herzen and even contributed for Kolokol. And after speaking to Herzen and seeing the power of a free word, Honcharenko founded in San Francisco the fortnightly Alaska Herald with the Ukrainian-language supplement Svoboda. It was 1868. Svoboda can be said to be the beginning of the free Ukrainian press in America.

“Ivan Franko’s works have dozens of references to Herzen. They are about not only, so to speak, Herzen’s Ukrainian motifs but also his freedom of the Russian thought. We will also find in the memoirs of Yevhen Chykalenko the proof that many Ukrainian liberals printed and read Herzen’s works at the time.

“We should not forget, either, Herzen’s achievements in literature. The Thieving Magpie was quite an event in Russian literature. And, in my opinion, My Past and Thoughts established intellectual traditions in Russian literature. Herzen ridiculed falseness and hypocrisy of the official religion which seemed to be turning christened people into its own property. In Kolokol, the theme of serfdom is of paramount importance. There are a lot of works about the brutalization of peasants by landlords. When I happened to write about Taras Shevchenko, I was astonished that present-day intellectuals allege that his works on serfdom are not much up to date and are not interesting for today’s schoolchildren. I advise the intellectuals who think so to read Kolokol, where one can find the answer to the question what serfdom is. Taras Shevchenko was respected all over Russia which called him the main fighter against serfdom.

“One of the main points in Herzen’s criticism of tsarist Russia was exposure of the military clique whose traditions are, unfortunately, still living today. Herzen wrote that the impetus Peter I had given to militarists was so strong that under the following tsars all positions were dished out to retired officers. Speaking about Nicholas I, Herzen said that his aim was to return to patriarchal and barbaric times of Moscow tsars, without losing the grandeur of the Petersburg emperorship.

“It would be good to read this quotation: ‘The state wagon that he drove bogged down in the snow up to the brim, the wheels stopped turning. No matter how hard he flogged his jades, the wagon wouldn’t budge. He thought he would improve things by means of terror. It was forbidden to write and travel, but it was allowed to think, so people began to think. The Russian thought received awful development in that dark hour, and if you compare its hidden influence and its fearless logic that does not pale at the sight of any consequences, with the young, noble, and purely French direction in literature over the past 25 years, you will clearly see this.” One more quote: ‘Our public opinion showed its tact, its preferences, and its relentless strictness even in the times of public silence. Whence is this fuss about Chaadayev’s letter, why this furor over The Inspector General, Dead Souls, Notes of a Hunter, the articles of Belinsky, and the lectures of Granovsky? And, on the other hand, evil wreaked vengeance on its idols for civil betrayals or unsteadiness. Gogol died of his own curse; Pushkin himself felt what it means to extol Nicholas. Our litterateurs were more ready to forgive laudations to the inhuman barrack-room despot than the public – their conscience was blunted with their refined esthetic palate!’

“You will agree that it is very much to the point in the realities of today.”

V.P.: “Incidentally, as far as Herzen and Ukraine are concerned, Herzen wrote about ten letters to Marko Vovchok. They had rather a close relationship.”

I.D.: “One of the important directions of Herzen’s struggle is Poland. It is interesting how he described the atrocities of the Russian soldiery. He begins with the ‘haidamaky-bashing Empress Catherine.’ Herzen notes that the tradition of the ‘haidamaky-bashing empress’ was upheld during the suppression of the 1863 uprising in Poland. He speaks of this in very harsh terms: the impoverished and wretched slaves were driven to Poland and allowed to rob Polish landlords and drink wine from their cellars. Then he quotes an official report that says: ‘Russian warriors have displayed the best qualities that should be inherent in every army,’ Herzen concludes this thought as follows: ‘My dear soldiers, please use your experience in Russia.’

“Maybe, no one else but Herzen has spoken of Ukraine so well.”

Newspaper output №:

№23, (2012)Section

Topic of the Day