Political cartoons: sharp, funny, and bitter

It so happened that political cartoons are rather infrequent in Ukrainian periodicals. In this respect, The Day does stand out: Anatolii Kazansky’s political cartoons have had a permanent place on the paper’s pages since mid-1990s – as a rule, it is the front page. This often determines the periodical’s political views and shows its opinion of this or another political character. Moreover, Kazansky’s cartoons remain topical even years after they were made. Well, like any work of art, caricatures can enjoy true longevity – for, being a genre of social and political essayism, it is often worth several feuilletons or pamphlets. By the way, both these genres have virtually sunk into oblivion as well.

“We do not have true political cartoon, despite the existing demand in society,” says the Perets magazine chief artist, Oleksii Kokhan. “However, there is no interest in this genre whatsoever on the part of publishers. Our politicians are afraid of even friendly caricatures, let alone the biting satire. Although I believe the cartoon to be a magnifying lens for our reality. And today’s reality is such as to offer more than enough topics for political cartoons. Moreover, there are artists who can make them.”

His colleague from the “satire guild,” People’s Artist of Ukraine Anatolii Vasylenko is not so pessimistic – maybe due to the facts that he is one of the few cartoonists who, since 2005, have had permanent commissions for political cartoons from the newspaper KyivPost and the magazine Correspondent. A book of his political cartoons is soon to be printed by Tempora Publishers.

“However, often there are instances when you have to soften the bitterness and smooth out the text,” admits the artist. “My cartoons are on the more aggressive, attacking side. But when it comes to political cartoon as a genre on the whole, in our country it is barely alive. Some cartoonists have to pile up their work: thanks to the old Soviet tradition, there still is demand for cartoons featuring drunkards, layabouts, and bad managers on the regional level, as well as family and everyday life subjects.”

All these dismal thoughts were inspired by the exhibit of American political cartoons, which lasted for several weeks at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine. The visitors had an opportunity to trace the development of this genre’s senses, philosophy, and artistic level over the recent 258 years.

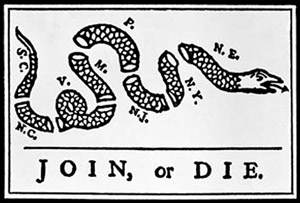

The evolution of political cartoon in Britain’s North American colonies was launched by a drawing by Benjamin Franklin, one of the United States “founding fathers” to be. His most famous drawing was published by Pennsylvania Gazette weekly in 1754, accompanying an article written by Franklin to urge Britain’s American colonies to unite against the French in the time of the French and Indian War. The cartoon shows a serpent, divided into several parts, each bearing the initials of one or another British American colony or region. The caption reads, “Join or Die.”

“This powerful call under such a, let’s be frank, crude drawing played then its historic role in uniting the former colonies,” said in a speech at the closing of the exhibit Eric Johnson, the US Embassy Counselor for Public Affairs. In the years to follow, hundreds of American cartoonists tried to influence various political situations in the country with their sharp, biting drawing. Many of them have left a trace in the US political history.

In particular, in the second half of the 19th century the nation’s most famous cartoonist was Thomas Nast (1840-1902), who worked for the Harper’s Weekly magazine. His work helped unmask some of the corrupt politicians of his day, against whom the artist launched an uncompromising campaign. In particular, Nast’s campaign against the New York City’s political boss William Magear Tweed is legendary. Cartoons of him and of his fellow politicians regularly appeared in the magazine. Voters ousted Tweed and his compatriots in November 1871. An irony of history is that when Tweed escaped from jail and fled to Spain in 1876, he was recognized and arrested by a customs official who did not read English but had seen Nast’s Harper’s Weekly caricatures of Tweed. Soon the runaway was jailed and died in prison.

Another example, important for us in the first place. Some in the US still believe that Nast’s another cartoon decided the fate of the 1884 presidential election in the States. The two contenders were the Republican former United States Senator James G. Blaine and the New York Governor Grover Cleveland, a Democrat. Five days before the polls, New York World’s front page carried a huge anti-Blaine cartoon. The Democrats spread it on thousands of billboards across the country, but mostly in New York City. Blaine lost the election, although he had every chance to win. He lost by a narrow margin, only 1,100 votes – and that was in New York City.

Cartoonists from a variety of periodicals participated in Barak Obama’s first presidential campaign. The Pulitzer Prize winner, editorial cartoonist Matt Wuerker drew a caricature featuring all the eight Democratic presidential candidates, the best-known of whom where Obama and Hillary Clinton. Each of them was portrayed doing some work: one ready to sweep the street, another to repair your car, the third to mow the lawn or clean your windows – all to get your vote. There was also an Iowa farmer in the picture saying, “I love convention time!”

By the way, the cartoon in the US is protected under the First Amendment to the Bill of Rights.

Of course, the drawings which were represented at the exhibition do not fully reflect the development of the American editorial cartoon. However, they prove that it has played an important role in the protection of democratic traditions. According to Stephen Hess and Sandy Northrop, authors of the American Political Cartoons, 1754-2010: The Evolution of a National Identity, laughter is a powerful weapon for a society which is choosing its leaders.

Newspaper output №:

№71, (2012)Section

Society