“On the Road to the Bright World”

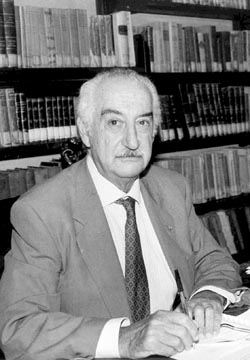

In memory of the Italian historian Gabriele De Rosa

That evening the Luigi Sturzo Institute was unusually quiet, with only one conference hall lit — and this in the merrily bustling center of Rome shortly before Christmas, with hospitably open shops and stores, sparkling garlands, and crowds of tourists milling about the Pantheon. The 15th-century structure with palms in the patio, ancient stairways, vaults with faded frescos. The Luigi Sturzo bust. The only illuminated hall.

Two years ago the place was agog with festivities marking the 90th birthday of Gabriele De Rosa, the patriarch of Italian history. Now there was a coffin with his body there. Wreaths and flowers bound by violet ribbons. His wife Sabine, a German from Poland, looking as if she was made of transparent glass. Another woman kneeling by the coffin and crying – his secretary of many years.

Gabriele de Rosa died on Dec. 9, 2009. Humankind lost a great scholar along with an epoch in the history of Europe of intellectual honesty. De Rosa personifies Europe the way it was visualized by generations of Eastern European intellectuals as they struggled against the communist regime, dreaming of the fall of totalitarianism when the two Europes would finally unite as a single entity of freedom and culture.

Gabriele de Rosa was born on June 24, 1917, in Castellammare di Stabia, a town not far from Naples. He graduated from a law school, took part in the resistance movement during the Nazi occupation, and was on the SS wanted lists. After the liberation of Rome, he joined the Left Christian Party and then the Communist Party of Italy after the LCP’s dissolution (1945). He withdrew in 1952 because he disagreed with its ideology. In 1992 he was elected as head of Christian Democratic Party. In 1987–94 he was a member of the Italian Senate and founded a chair of contemporary history for the first time in the history of the Italian university.

He taught contemporary history at the universities of Padua and Salerno (he was the rector of the University of Salerno in 1964–74), as well as at the Sapienza University of Rome. In Padua he founded the Veneto Regional Church History Study Center (1966). Later it was transferred to Vicenza (1975) where it became known as the Institute for Social and Religious History Studies. De Rosa was secretary general of this institute (1975–99), its president (1999–2006) and honorary president in the twilight of his life. In 1979–2007 De Rosa was president of the Luigi Sturzo Institute in Rome, one of Italy’s most prestigious institutions of higher learning.

Luigi Sturzo and Gabriele De Rosa. Combined, these names have a profound symbolical meaning. In 1954–59 De Rosa collaborated with Don Sturzo who was a noted Italian religious figure. In fact, Luigi Sturzo was an ordained Roman Catholic priest, also an antifascist/anti-Nazi philosopher. After emigrating from fascist Italy to London and then to New York, he kept waging a consistent struggle against the 20th-century totalitarian regimes, siding with the oppressed peoples. The civic context of his activities is strongly reminiscent of the founding fathers of Europe, among them Robert Schuman, Konrad Adenauer, Alcide De Gasperi, Altiero Spinelli, and Jean Monnet. This collaboration with Don Sturzo (De Rosa was also Sturzo’s and De Gasperi’s biographer) served as an important intellectual asset for De Rosa’s research. Sturzo, for one, was sharply opposed to Europe being divided into spheres of influence; he was all out for all peoples of Europe (except those of the Baltic States) to be able to exercise their right to self-determination; he saw Europe not as a product of bureaucratic procedures, but as a great cultural project rooted in antiquity and humanist civilizations.

Among De Rosa’s scholarly investigations are essays on the history of churches in southern and northern Italy, Catholic, Papal Movement in conjunction with the life of society and political process. One of the major trends of his research has to do with the lives of saints and religious cults (primarily in southern Italy). This actually boils down to the people’s religious history. The philosophy of His grace, miracles, forgiveness, treated as a subject of scholarly investigation, emerges not as a mysterious “pause” in current realities, but as a deep-reaching social answer to man’s innermost spiritual questions. What makes De Rosa’s religious historiographic method innovative is his concept of vissuto religioso, religious empathy with reality, that allowed him to study church history being inseparably linked with the development of civil society; also, the conceptual ethical grounds for the historical and cultural unity of Europe as a continuum of Christian civilization.

De Rosa raised the matter of the moral role being played by history and its responsibility for the way of life today. Sturzo taught: “Man is bound by the land; his life is on a local basis; he travels across the world, but his ties with his sentiments, habits, and interests are never severed, for all this is rooted in his origin: home, people living next door, landscape, acquaintances, friends, even enemies — all this is that small world that forms… the big world for us… all the way from a separate village to the nation as a whole.”1 Hence this religious empathy for reality. With De Rosa, this is a family-like, authentic, the most keenly perceived dimension of one’s homeland. He says that these are “local things” rather than a “history of belfries”; this is a “history of human space that doesn’t exist separately but as part of that whirlpool of interests and feelings…”2

In this sense, he doesn’t accept history as a record of events and facts — even less so superficial theses like those about “the end of history.” History is not a record of a sequence of events in the course of ideological struggle. Rather, it is a record of major transformations in the conditio humanitatis, human condition. Only this humanist approach to history allows one to avoid being afflicted with “historical fatigue,” getting lost “in the blizzard of time,” and enables one to tell about time as a great saga of human existence. Now compare this to the attitude to the Fatherland being practiced in Ukraine — or to the process of re-Stalinization of history being practiced in Russia. Regrettably, here one stumbles across a vivid cultural boundary line separating the “Old” and “New” Europe.

Back in the 1980s-1990s, De Rosa focused on Eastern Europe, coming up as one of the Italian and Western European promoters of the idea of Eastern Europe’s necessary integration into a united Europe. Owing to his close collaboration with the Italian Slavist Sante Graciotti3 and Polish historian Jerzy Kloczowski4, De Rosa helped promote Polish studies in Italy, among other things assisting with the establishment of an Italian-Polish School at the Sturzo Institute to help Polish university graduates.

This took place in the late 1980s, with Solidarity’s ideas blossoming, shortly before the collapse of the Berlin Wall. He organized the symposium “Underground Religion in the Countries of the East” in Treviso (1990). It was attended by scholars from Lithuania, Poland, Hungary, and Croatia. It was then that the Church emerged as a victim of communist persecution, now a bulwark of spiritual struggle against totalitarianism.

In his twilight years, De Rosa took a keen interest in Ukraine, so the Vicenza Institute’s social and religious study center focused on Eastern Europe. This was an unexpected shift in the institute’s scholarly attention, considering that it previously focused on Veneto religious studies. De Rosa’s inexplicable gifted historian’s insight must have been at play. He must have realized that here was a field never actually cultivated before. In addition to cultural and historical data available, albeit little known in Europe, he visualized Ukraine as an inseparable component of the Old Continent’s dynamics. He regarded Ukraine’s European integration as a major factor of cultural enrichment, as the formation of a new identity in Europe.

De Rosa started acting as a promoter and organizer of a number of important scholarly meetings and symposiums, including the roundtable “Polish-Ukrainian University: Between the Past and the Future of Central-Eastern Europe” (Sturzo Institute, Rome, 2003); the international symposiums “Old Kyiv Epoch and its Heritage in Meeting with the West” (Vicenza Institute for Studies of Social and Religious History, 2002); “Injured Humankind: 20 Years after Chornobyl” (ibid., 2006).

Doubtlessly the most important event was the international symposium “The Death of the Land. The Great Famine in Ukraine, 1932–33,” which took place at the Vicenza Institute in October 2003. It was held under the patronage of the Italian President Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. This symposium marked the beginning of a number of scholarly and political initiatives aimed at deepening the investigation into the Holodomor. This symposium adopted a statement addressing the Italian parliament and the European Union, demanding that the Holodomor be recognized as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.

Incidentally, this was the last time I saw James Mace. His health was visibly failing him, yet he wouldn’t miss a single meeting. I remember his enthusiasm after the conference. This is how Ukraine’s integration was taking shape, he said. We said good-byes by a windmill built 500 years ago. Who would have thought that this was our last meeting?

Among the results of these symposiums were two important publications edited by De Rosa that gave a fresh impetus to Ukrainian studies in Italy, launching the Media et Orientalis Europa (Central and Eastern Europe) series: L’Еta di Kiev e la sua eredita nell’incontro con l’Occidente (Kyiv Epoch and its Heritage in Meeting the West, Rome, 2003) and La morte della terra. La grande “carestia” in Ucraina nel 1932-1933 (Death of the Land. The Great Famine in Ukraine, 1932-33, Rome, 2004). A collection of findings of the Chornobyl symposium is now being prepared for publication.

Among De Rosa’s most important works along the lines of Ukrainian studies one ought to mention “Terra Incognita in the Heart of Europe,” “Ukraine, with Historians Keeping Silent,” “Polish-Ukrainian University between the History and Future of Central-Eastern Europe,” “Historiography in the Process of Construction,” and “Europe and the Holodomor in Ukraine.”

This Eastern European trend in De Rosa’s studies results from his nonconformist attitude, the impassionate civic orientation of his singular talent, his ardent desire to refute conventional interpretations of problems and replace them by in-depth research. For as long as he lived, De Rosa remained true to his principle of “religious experience of reality.” After focusing on Ukraine, he decided to travel to Kyiv as a pilgrim. Mykola Zhulynsky helped with arrangements. His colleagues later said that this trip was actually an act of pilgrimage rather than a visit. De Rosa wanted to touch the religious relics of Kyiv and perceive their full meaning. St. Sophia’s Cathedral and the Kyiv Caves Monastery — he visited them, although by that time he could hardly walk unaided. He used a cane and had to sit on a chair every ten minutes (this folding chair was carried by our interpreter Andrii, who accompanied him). Anyway, he did his pilgrimage.

De Rosa’s academic research was always accompanied by a humanitarian context. Francesca Lomastro, Vicenza Institute’s veteran medievalist, also works for the Il Ponte Association. Every year she is busy with health-building projects for Chornobyl children. Every such project calls for a Herculean effort, among other things owing to the ruthless red tape on both sides — suffice it to mention the visa procedures. Yet even here there is no impassable real-life-academia boundary line.

At present, among Vicenza Institute’s numerous Eastern European research projects is one entitled “Parentless Childhood from the Middle Ages to the Present Day. Comparative Analysis of Italy and Ukraine.” The most important of the planned projects has to do with democracy and religion in Eastern European countries. In-depth research endeavors are being made in Central Asia, with a team of researchers studying the history of religion in Kazakhstan. A book entitled “Stalinism in Borderland” was recently published. It demonstrates how Stalin worked out terror famine techniques before the Holodomor in Ukraine by annihilating Kazakhstan’s Bedouin culture. Dr. Giorgio Cracco, De Rosa’s successor as the institute’s director, is Full Professor of Ecclesiastical History at the Faculty of Political Sciences of the University of Turin (since 1988), and for him studies of Ukraine and Eastern Europe are among his scholarly priorities.

Works by Gabriele De Rosa have been translated into English, German, and French. The author won numerous Italian and international academic awards. In 2006 he became an honorary member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

The funeral ceremony took place at St. Augustine’s Church, named after this celebrated medieval philosopher whose understanding of time relied on the concept of the “present time of the future.” History was for De Rosa a science of the future. During the Mass for the Dead, Cardinal Achille Silvestrini said: “De Rosa was a man who always had the courage of the truth.”

We felt sad after the funeral, realizing that the world had lost yet another great soul, but De Rosa left behind his behest, the imperative of working hard. I stood there with a group of Vicenza Institute people and gradually we started discussing new projects aimed at overcoming misunderstandings between Eastern and Western Europe.

At the outset of our collaboration Francesca Lomastro was the promoter and organizer of an exhibit of Ukrainian works of art dating from the turn of the 20th century, including those dated September-October 2004, shortly before the Orange Revolution. This exhibit was entitled “On the Road to the Bright World.” The bright world is probably something you need to remember when you are grief-stricken, for it means great expanses where you can meet people you love, where there is lasting light of supreme wisdom.

De Rosa would always say, Che ti accompagni la Madonna — May Our Lady be with you! — a traditional phrase in southern Italy. He passed away on December 8, The Day of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. May the Madonna guide De Rosa in his future life. We will do our best to use his creative heritage to disseminate in Europe the new kind of knowledge about Ukraine.

Oxana Pachliowska holds the Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the Department of Slavonic Studies, La Sapienza University of Rome, and is on the staff of the Department of Ancient Ukrainian Literature at the Institute of Literature (Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences, Kyiv).

1 Cit. in: G. De Rosa. Che cosa puo dirci oggi la parola di Luigi Sturzo? // L’appagamento morale dell’animo. — Roma, 2007. — P. 358.

2 Cit. in: G. De Rosa. A venticinque anni dalla fondazione dell’Istituto di Vicenza // L’appagamento morale dell’animo, op. cit. — P. 208.

3 Dr. Santo Graciotti is an old friend of Ukraine who is especially interested in the Ukrainian Baroque period. He visited Kyiv recently to attend the symposium “Nikolai Gogol’s Magic Influence on the World and Ukrainian Cultural Progress” (part of the Maria International Festival — see his interview “Ukraine’s Cultural Mission” (No. 168, Sept. 22, 2009; “The Power of Pluralism” (“Ukrainian Week”), No. 41 (102), Oct. 9, 2009; Graciotti’s report on Gogol, entitled “From the Homeland by Blood to the Homeland by Spirit,” as well as S. Marchenko’s article “That Was a Different Kind of Fatherland and Different Times” (Kultura i zhyttia, No. 39, 2009)

4 Jerzy Kloczowski is a Polish historian, medievalist, professor at the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, director of the Central and Eastern European Studies Institute. He has authored numerous monographs dealing with Polish culture, the interrelationships between Western and Eastern Europe, largely focusing on Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania, regarding these countries as an inseparapable part of Polish-European dialog.