Two rivals

The 14th century: Moscow and Tver vying for the Grand Principality of Vladimir

A historian resembles a gold digger (how much useless sand he has to patiently sift in search of the coveted grains!) or a methodical astronomer who processes for years and decades the data that his “eyes” supply (incidentally, the sources of these signals, as well as the facts that the historian operates, are a very long distance away from us – a star may have been extinct for a million years, but its light reaches Earth only now). Therefore, a historian, even a serious and scholastic one, is always, to some extent, an “investigator” of the mysteries and puzzles that come up on his scholarly path, a seeker of the way in the intricate maze of versions, hypotheses, and suppositions. Niels Bohr, the Danish genius of the 20th-century physics, said that his science (an exact science, incidentally) was always based on the “escape from surprise,” i.e., the intention to explain something rationally and in our typical way of thinking what seems to be unexplainable. This idea of his also applies, to a large extent, to historical science – provided that one shows due respect for documentary sources.

Let us try, reader, to find the answer to not so obvious a question: why was it the Principality of Moscow and not one of its numerous rivals that became the center of “land gathering,” the hub of a political entity that promoted the formation of the Great Russian nationality in the 14th-15th centuries? In search for this answer, we will travel to the 14th century (its first half, to be more precise) which is often called “dark” due to a dearth of written sources and, all the more so, proven facts. As we will see, this very century conceals a lot of interesting things.

To begin with, let us briefly describe the geopolitical (in modern terms) position of the principalities of Zalesye (“place beyond the woods”), also known in Soviet historiography as North Eastern Rus’ or Vladimir-Suzdal land, and the territories they controlled at the very beginning of the 14th century. There were quite a few of these principalities: of Tver, Riazan, Moscow, Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod, Gorodets, to name just the largest of them. But the “senior” prince of the “entire land” was the one who had received a yarlyk (permit) from the Golden Horde khan to be the Grand Prince of Vladimir. The latter used to be solemnly enthroned in Vladimir-on-Kliazma [now the city of Vladimir. – Ed.] at the Dormition Cathedral built by Andrei Bogolyubsky and Vsevolod the Big Nest in the late 12th century. They were therefore called Grand Princes of Vladimir, even though they continued to rule in their own cities in reality, i.e., Nizhny Novgorod, Tver, Moscow, etc.

Incidentally, one should take into account two more factors to be able to properly understand the events of that epoch. Firstly, all the abovementioned princes launched a competition of sorts in the early 14th century for the largest bribe to be given to the Horde khan for the grand princedom yarlyk. And the powerful khans Tokhta (reign 1291-1313), Uzbeg (reign 1313-1343), also known as Avziak, Ovziak in Moscow and Tver chronicles, and Jani Beg, during whose reign the Golden (Volga) Horde achieved the peak of prosperity, willingly encouraged this bidding, for they found it lucrative indeed. Secondly, the first half of the 14th century (to be more exact, 1323-49) is the time of the decline and fall of the Ukrainian Principality of Galicia-Volhynia: this entity ceased to exist under the pressure of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (in fact a Lithuanian-Ruthenian state). The ethnic Ukrainian territories found themselves divided between the two “winners.”

As for the recently Slavicized Vladimir-Suzdal, Moscow, Tver, and other Upper Volga regions (including the feudal republics of Great Novgorod and Pskov), the Mongol-Tatar rulers quite successfully applied a well-tested and old as the hills divide et impera [divide and rule. – Ed.] method by setting some princes against the other and maintaining a smartly-calculated “balance of forces.” For example, even the possession of Grand Vladimir princedom yarlyk did not guaranteed the “lucky man” any strong political power because the Golden Horde’s grand khan often deliberately backed his main rival in order to balance the scales.

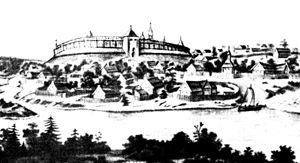

At first, the Horde, naturally, preferred Tver owing to its central location in the entire Volga region (a huge Volga trade route that was of importance for Eastern Europe). Tver was a suitable gate to Novgorod, western Rus’-Lithuania principalities, and Lithuania. But, in the course of time, this advantage of geographical position became an obstacle to it becoming a state-building center because proximity to the Lithuanian-Ruthenian center made Tver dangerous to the Horde.

It is under those circumstances that Moscow began to rise. Far from all its rivals took it seriously at first (for example, in 1301 one chronicler described the future capital of terrible and despotic tsars as “a small insignificant town”). At the expense of what did this “town” gain so much strength? Many pointed out – not without a reason – the advantageous location of Moscow that was protected from hostile Horde forays with forests, hills, and river floodplains. This was, undoubtedly, an essential factor. But we think something else was more important. Muscovite rulers knew how to make a deal with Golden Horde khans, whereas Tver princes very (and unjustifiably) often challenged them with arms. And the Mongol warlords, first of all, the abovementioned Khan Uzbeg, finally staked on Moscow after much thought and consideration (as wise diplomats, they understood that it would be wrong “to put all their eggs in one basket”). Khan Uzbeg established very good relations with a Muscovite prince (later the Grand Prince of Moscow and Vladimir in 1328-40) known as Ivan Danilovich Kalita. Uzbeg and Kalita got on very well, which, as we will see, had serious consequences for the further course of history.

It is known that Tver Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich, the nephew of Alexander Nevsky, was summoned to the Horde in 1319, condemned to death by Uzbeg, and executed. A considerable number of historians believe this was done with the active help of Moscow Prince Yury Danilovich, a grandson of Nevsky, who had been smitten hip and thigh by Mikhail at the Battle of Tver in 1317 and therefore deeply hated him. Yury Danilovich (incidentally, a close relative of Uzbeg, married to his sister), had successfully lodged several denunciations against the prince of Tver, claiming that he was the sworn enemy and hater of the Horde, which resulted in a tragic destiny of Mikhail – this prince, the most powerful ruler of Vladimir and Suzdal lands, paid for this with his own life. After this, the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir went to Yury Danilovich of Moscow, who, in his turn, was also killed in a blood feud by Mikhail’s son Dmitry (the Horde had him beheaded for this).

Interestingly enough, chronicles mention almost no high-profile uprisings of Muscovites against the Tatars in the first half of the 14th century. On the contrary, historians know very well from the chronicles about the famous Tver uprising in 1327, when Alexander, the younger son of the executed Mikhail, was the Grand Prince of Tver and Vladimir. What provoked this uprising was the boundless atrocity and impudence of Khan Uzbeg’s cousin Chol-Khan, alias Shevkal (Shchelkan in Tver chronicles).

The following extract from a song of those times is about him:

“He, young Shchelkan,

Collected tribute and heavy taxes.

He would take a hundred rubles

from a prince,

Fifty from a boyar,

And five from a peasant.

If one had no money,

He would take his child away.

If one had no child,

He would take his wife.

And if one had no wife,

He would take his head away.”

A rebuff was inevitable. Here is what the so-called chronicler of Rogozh says: “But the lawless Shevkal, the ruiner of Christianity, went to Rus’ with many Tatars and came to Tver. He drove away Grand Prince Alexander Mikhailovich from his court and established himself there. Full of great pride and fury, he began a wide-scale persecution of Christians, resorting to plunder, beatings, and desecrations. The Tver residents endured humiliation from the pagans all the time and repeatedly besought Grand Prince Alexander Mikhailovich to protect them. He saw how embittered his people were, but he was unable to defend them and told them to put up with it, But the Tver people could not endure this and only waited for a suitable time.

“This happened on August 15 [1327. – Author] early in the morning, when the marketplace was full of people. A Tver deacon named Dudko led a young and very fleshy mare to the Volga river to drink water. When the Tatars saw this, they took the mare away. Then the deacon began to shout loudly:

“‘Oh, Tver men, come to help me!’

“And there was a fight between them. Hoping that they would go scot-free, the Tatars began to flog him. And people immediately gathered and went into turmoil, all bells began to ring, and the whole town rose up. All the people came over and rebelled. The Tver people yelled a call to arms and began to beat the Tatars. They kept killing everybody they caught until they killed Shevkal himself. They beat everybody they could see and left nobody alive, even the messenger, except for the shepherds who grazed herds of horses in the field. The latter grabbed the best stallions and made for Moscow [as you, reader, will see, not accidentally ‘for Moscow.’ – Author] as fast as they could and thence to the Horde, where they announced the demise of Shevkal.”

This is the end of the chronicle evidence. And now see how quickly Prince Ivan Danilovich of Moscow, Yury’s brother, nicknamed Kalita (a small bag or purse to put money in – an eloquent nickname indeed!), acted. On hearing about the tragic events in Tver (and knowing very well that the Tatars will not forgive this), he immediately rushed to the Horde’s Khan Uzbeg and “offered his services” to crush the uprising with fire and sword. A united force of the Mongol-Tatars and Kalita’s men took Tver by storm: they reduced the city to ashes (it never managed to restore its erstwhile power), ruined and sacked the Ryazan and Nizhny Novgorod lands. Only Ivan Kalita’s Moscow Principality was left absolutely intact. It is a very telling fact because, from then on, this principality was only gaining strength. As a chronicler says, in 1332, Kalita, by then the Grand Prince of Moscow and Vladimir, was officially put above all the other princes: “the tsar [Khan Uzbeg. – Author] vested him with power to be the grand prince of all Rus’ lands, as was the case with his great forefathers.” Kalita also managed to make a deal with Uzbeg (for he had won the bidding for the yarlyk, albeit at a terrible price), under which he had an exclusive right to collect tribute for the Horde, bypassing Tatar collectors, and hand it over the khan personally. As a result, 40 years later, the once little town of Moscow became, perhaps, the only principality that remained strongly protected from Tatar or any other enemy invasions.

And the attached map of “gathering lands” around Moscow is a good illustration of what happened afterwards.