The long way of memory

Larysa Skoryk’s studio presents the design of a memorial complex in Babyn Yar

Each of us has some significant places that are linked with certain events in our own life or even places where you feel yourself part of the country and its people, where the human community once had an unheard-of spiritual upsurge or precipitated into the abyss.

Babyn Yar is this kind of a sore point in Kyiv – a black tragedy staged by the invaders from September 29, 1941, onwards. For years to come, the blood of the criminally killed innocents seeped through the ground there, while the Soviet state’s “fair” policy actively resisted the natural desire of people to honor the victims’ memory. There were also a lot of those who fearlessly struggled to preserve this memory – suffice it to recall a prompt banishment of the true patriot and writer Viktor Nekrasov. Then the time came when not only the common people but also official delegations, national leaders, and high-ranking guests began to visit the monument to Babyn Yar victims and the Menorah, bowing their heads in memory of their compatriots.

Attempts have been made from time to time to establish an integrated Memorial Complex. The ideas range from Soviet-era-style gigantic monuments to hotels and entertainment centers that appeal so much to present-day businesspeople.

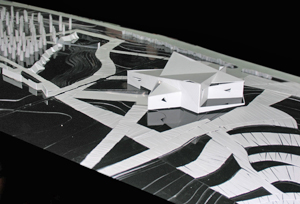

The design submitted by Larysa Skoryk’s studio to the Cultural Heritage Advisory Board of Ukraine’s Ministry for Culture is distinguished not only by Skoryk’s own refined architectural style, tolerance towards the victims and those who saved them at a risk to their own and their relatives’ life, but also by a profound emotional and ideological meaning. The space is filled logically and laid out in an extremely neat way. The road will have visitors pass by the place where Olena Teliha and her comrades were killed – a place dear to the heart of every conscientious Ukrainian. Then more than 600 evergreen name-plated trees will be planted in the Garden of the Righteous. The latter and the restored fragments of the Memory Wall, once created by Ada Rybachuk and Volodymyr Melnychenko, will be connected with the Alley of the Righteous of the World, where there are 2,600 nameplates – an international army of those who would save the Jews in various points of the world.

“This is a sacred territory that should remain the way it is, but it should also include the Babyn Yar Memorial Museum,” Larysa Skoryk said.

According to the designers’ concept, the museum building’s level will be lower than that of the memorial garden and alley – it will seem to soar in the air like a broken six-pointed star. And a special backlight will make it easy to see and recognize it from a bird’s-flight height. Every visitor will be leaving the museum all alone, walking on a narrow glazed bridge over an abyss. And, when the visitor is up, s/he will proceed past the lapidarium to a small chapel dedicated to the memory of the Orthodox priests who also took part in saving the people to be killed in Babyn Yar.

When I was listening to a self-confident and emotional Skoryk and her professional colleagues, the board members, who benevolently showed interest in and accepted the original design, I thought that carrying out this project would help better than any pompous phrases and promises to inscribe us, citizens of Ukraine, into the civilized world community which knows how to pay tribute – respectfully, strictly, and finely – to memory, i.e., to remember its own self.

The design was approved by the General Architectural Directorate. All we have to do is to wait for a feasibility report to be drawn up, all the other problems to be settled, and the excellent idea to be put into practice.