“A tree with its top lopped off”

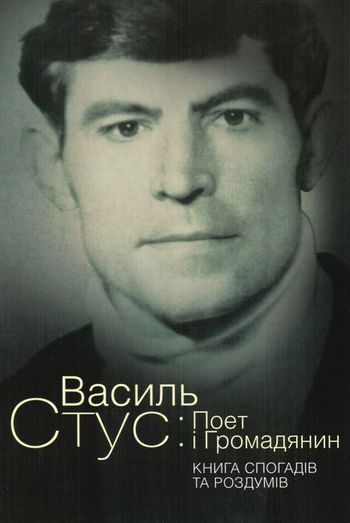

Recently, the Museum of Books and Book Printing of Ukraine held a creative evening of the famous ex-dissident, human rights activist, historian of anti-totalitarian resistance, journalist Vasyl Ovsiienko, dedicated to the recent release of the book of memories and reflections Vasyl Stus: Poet and Citizen, of which Ovsiienko was the compiler.

The evening, too, was focused on memories of life, creative achievements and anti-regime struggle of Stus who was one of the greatest Ukrainian poets of the 20th century. During the event, Ovsiienko often recited Stus’s poems, including those rarely published or included in readers. “I heard Stus himself reading poetry in the prison cell which he shared with us,” the ex-dissident told the audience. “You know, it sounded very differently from tape recordings that are well-known today.”

At the beginning of the meeting, participants saw an excerpt from the film Black Candle of the Lightening Road. It is the first documentary about Stus. Stanislav Chernilevsky started shooting it back in 1989. Some of the production took place in the village of Kuchino in the Urals, in the labor camp where Ovsiienko had served his term, and Stus died. The camp had already been closed by the time, and its buildings were half-ruined, but some memorabilia could still be found there, including a note hidden a few years before, keys to cells (including the one where the poet perished), pieces of convict uniforms, and parts for clothing irons which prisoners produced. Ovsiienko brought these telling historical exhibits to his presentation so that the audience would hear the unwieldy camp keys clank.

In his speech, Ovsiienko covered Stus’s childhood as well as his development as a poet and fighter for justice, putting interesting biographical details in it. For example, he told the story of dissident families’ frequent trips to Prypiat River, where Stus once dressed as a vodianyk [water spirit from Slavic folk mythology. – Ed.] and plied the river in a boat with children playing the part of poterchata [vodianyk’s helpers, said to be recruited from ghosts of unbaptized children. – Ed.], scaring people in oncoming boats.

Of course, he covered Stus’s arrests, trials, and periods of imprisonment. He recalled, in particular, the role of Stus’s defense attorney Viktor Medvedchuk, currently known as a pro-Russian politician:

“Many say that Medvedchuk could not protect Stus, so he was not at fault then. But I want to remind you that in his speech for the defense, he said that his client deserved to be punished for all his ‘crimes,’ and just asked the court to take into account mitigating circumstances, that is, Stus’s fulfillment of his quota at the plant where he worked, and the surgery which he had underwent shortly before the trial. Medvedchuk did not even tell Stus’s wife that the trial had started. You know, not all attorneys acted this way. For example, my attorney demanded my release and action against the police officer who brought a slanderous accusation against me. Other attorneys passed information and notes with detainees’ final words to their families. Lidia Huk’s active lawyer, whose name was, by the way, Ivan Yezhov (so he shared surname with an infamous Stalin’s henchman), won early release for her. Thus, attorneys of the time, even though they were cogs in the system, always had some choice of how to act.”

Vasyl Stus: Poet and Citizen includes texts about its main character written by as many as 74 authors, including 9 foreigners. In fact, as noted by Ovsiienko, prisoners and dissidents of all nationalities treated Stus with great respect. For example, Mikhail Heifets from Leningrad learned by heart a great selection of Stus’s poems during his imprisonment, and then wrote them down as best he could in Russian letters. In this way, an important part of the poet’s literary legacy was preserved for the posterity. “That was real internationalism!” Ovsiienko summed up this story. “But, unfortunately, we were unable to preserve all the poems he created at the camp. Stus’s last notebook contained much free verse, and these poems perished in captivity. They were difficult to learn by heart as well... It was the reason for Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska to call Stus’s legacy ‘a tree with its top lopped off…’”

The human rights activist recalled also an unusually cheerful event in the camp, when “the first lifetime monument to Stus” was erected. Political prisoners called so a snowman which they built in a spare moment: “Stus saw his stay in the camp as not only time of suffering, but also an important step in hardening of his spirit. He said: ‘I used to be an Ukrainophile, but Mordovian camps have made me into a real Ukrainian.’”

Ovsiienko called some of Stus’s poems a sentence against the Soviet empire: “He felt its coming end, and now we see the empire’s death throes. However, its agony is a prolonged one, and it is still trying to bring peoples of Ukraine and Belarus in its fold again. I see that not all Europeans are aware that Europe’s fate is now decided on Maidan. If all of a sudden they succeed in recreating a strong empire, one should expect Russian tanks on the streets of Paris and Berlin. Meanwhile, Europeans try to talk to gangsters like those were normal people.”

Ovsiienko’s concerns about the European Union are more than understandable, especially in the context of the new German foreign minister’s recent interview, worthy of the Munich appeasers of 1938, or shockingly naive article by the head of Deutsche Welle’s Russian service.

Lirnyk Yarema, whose real name is Vadym Shevchuk, set the musical focus of the meeting by performing the old duma, Slaves’ Lamentation. Ovsiienko concluded the evening with the following maxim: “People want to see flawless and courageous leaders. Stus was one. Remember that the honor of a nation consists of all its members’ individual dignities!”

After the meeting, Ovsiienko commented on current developments in Ukraine exclusively for The Day:

“Maidan protesters are doing everything right! I am fascinated by our people, particularly impressive is the high level of self-organization. They have no commanders, yet everything gets done: someone brings snow to the barricades, someone prepares food, someone transports needed supplies. There is no police there, yet it is well-ordered, and even when a drunk appears there, they are calmly expelled. Honestly, I did not expect this. It is sometimes scary to watch the protests on TV, but it is not scary at all when one is there. I am sure we will win, but do not know when and at what price. But I feel that it will be soon. Ukrainians do not deserve Yanukovych’s style of government. We are a freedom-loving people.”