The Slavist from Oleksandriya

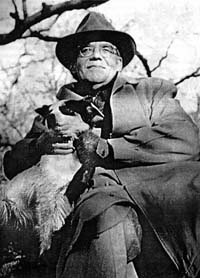

Dmytro Chyzhevsky was a philosopher, historian, and Slavist of encyclopedic knowledge; a brilliant and extraordinary researcher, who was endowed with astonishing talents and was entirely devoted to scholarship. Fate decreed that Chyzhevsky, who was born in Ukraine and considered himself a Ukrainian, would live and work abroad for almost his entire life. He is still abroad in a figurative sense, for most of his scholarly works have yet to be translated and published in Ukrainian. For this reason, Chyzhevsky is better known today in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Germany than in his homeland. He made a distinguished contribution not only to Ukrainian but also to worldwide culture. The Ukrainian American scholar Osyp Danko once said, “If somebody made a serious attempt to study the contribution that foreign-based Ukrainians have made to worldwide research, Dmytro Chyzhevsky, Professor of Slavic Philology at Heidelberg University, Germany, and director of the Institute of Slavic Studies at the same university, would undoubtedly occupy the most prominent place in the small group of Ukrainian researchers who have made such a contribution. In terms of Slavic studies, Prof. Chyzhevsky occupies the highest place not only among Ukrainian scholars but also among all Western Slavists.” As has been said many times, “You cannot be a prophet in your own country.”

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

Dmytro Chyzhevsky was born in Oleksandriya (now Kirovohrad oblast) in 1894 to the noble family of retired officer Ivan Chyzhevsky, who had served a two- year prison term in the Peter and Paul Fortress for belonging to one of the Narodniki (Populists) secret organizations. Later Ivan Chyzhevsky took an active part in the zemstvo (elective provincial council — Ed.) movement and joined the Party of Constitutional Democrats (Cadets). Dmytro’s mother was a teacher and artist, a pupil of Chistiakov and Repin. Dmytro was a student at the universities of St. Petersburg and Kyiv: in the latter he studied philosophy and Indo- European and Slavic linguistics. In pre-revolutionary Kyiv he participated in students’ and workers’ societies, was an active member of the Menshevik Party, representing it in the Little Rada of the Ukrainian government in 1918; there was a real prospect that he would become Ukraine’s minister of labor. Concurrently, he taught philosophy at Kyiv University and linguistics at the Higher Women’s Courses. When the Bolsheviks occupied Kyiv, the young Chyzhevsky was arrested and sentenced to death. Luckily, he escaped punishment. The 27-year-old scholar left his homeland and, like hundreds of thousands of others, he became an eternal emigre.

ABROAD

The emigre Chyzhevsky lived in many countries: Czechoslovakia, the US, but mostly in Germany, which he soon grew to cherish as his second homeland. Yet, in his personal and academic life he never forgot about Ukraine and never identified the Ukrainian language, statehood, history, and art with Russia’s. After abandoning politics for good, Chyzhevsky only shared scholarly interests with Ukrainian-born political emigres. He always cultivated a very hostile attitude to the Soviet Union: he could never forgive the crude Bolshevik repression to which he had nearly fallen victim.

Shortly before the Second World War, Chyzhevsky’s wife and daughter left for the US, while he, together with his students and books, remained behind in Germany, despite “being sullied by Jewish family connections” (his wife Lidia Marshak was a Jew). Chyzhevsky continued to teach at the university and pursue his scholarly research. It was in those years that he made an important discovery: searching in library archives, he found the manuscript, missing for 200 years, of De Rerum Humanorum Emendatione Consultatio Catholica, the main philosophical and pedagogical opus of Jan Amos Komensky (Comenius), the outstanding 17th-century Czech teacher and philosopher whom Chyzhevsky considered “the only Slavic thinker of worldwide acclaim” (although he placed some other figures, including Hryhory Skovoroda, on a par with him). His work on preparing the manuscript for publication brought Chyzhevsky renown as “the leading and most prominent Comeniologue.”

As soon as Chyzhevsky settled abroad, he immediately began to forge links with Ukrainian emigre educational and research institutions, including the Ukrainian Free University. In the 1920s Prague attracted a large number of outstanding Ukrainians, such as D. Doroshenko, M. Shapoval, M. Hrushevsky, et al; the Drahomanov Ukrainian Higher Pedagogical Institute was also located in the Czech capital. Chyzhevsky contributed to dozens of Ukrainian, Russian, Czech, Polish, French, and German journals, and published numerous works, e.g., Logic; Philosophy in Ukraine: an Attempt to Formulate the Historiography of the Question; Essays on the History of Philosophy in Ukraine; Greek Philosophy before Plato; The Crisis of Soviet Philosophy; Hegel and Nietzsche; and others. Through his efforts and scholarship, Professor Chyzhevsky helped found the Institute of Slavic Studies in Halle, Germany, which he hoped would become the world center of Slavic studies.

Chyzhevsky continued to broaden the circle of his scholarly interests. In the prewar years, when he was residing in Halle, he studied the comparative history of Slavic literatures and the history of Czech Church Slavonic literature; he made an in-depth study of the baroque style of Slavic literatures (the grateful Slovaks awarded Chyzhevsky the title “ honoris causa compatriot”); he also analyzed the works of Hryhory Skovoroda, Taras Shevchenko, Aleksandr Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, and Karel Capek; and devoted special attention to the history of Old Rus’ literature in the 11th-13th centuries, the history of 16th-century Ukrainian literature, etc.

POSTWAR YEARS

The Nazis’ rise to power and the ensuing war caused difficulties in publishing: Chyzhevsky published some of his articles under the pen-name of Fritz Erlenbusch, while other works were published dozens of years after they were written; many were lost forever. Despite these hardships, Chyzhevsky worked indefatigably. Slavic specialists would be hard put to name an area in Slavic studies to which he did not make a contribution. In 1945, a few days before Halle was captured by the Red Army, the scholar left the city, leaving behind his unique multilingual scholarly library, which the Soviets immediately confiscated.

This was an irreparable loss for Chyzhevsky because books were by far the most important part of his life, scholastic pursuits, and leisure. His German friend, Prof. Hans-Georg Gada-mer, wrote, “I often visited him. Every time I came to his house I had to go to the kitchen in search of a chair because all the chairs in the room were stacked with mountains of books.”

In 1945-1949 Chyzhevsky lived in Marburg, where he founded and conducted a seminar on Slavic studies at the local university. After the war, when humanity was divided into two hostile camps, Chyzhevsky attached great, even symbolic, importance to this seminar. He also actively participated in the postwar restoration of Ukrainian higher educational and research institutions in Germany, taught philosophy and logic in the Ukrainian Orthodox Theological Academy, regained the title of Professor of Philosophy at the Ukrainian Free University, and was a cofounder of the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences.

IN THE US

Despite all these efforts, the postwar West German scholarly administration took a rather cautious attitude to Chyzhevsky. The researcher was the object of intrigues and suspicions, and was even accused of being a “communist” (an official investigation was held into his “espionage activities,” which completely vindicated the professor). The difficulties of postwar life, malnutrition, and even starvation, as well as a shortage of scholarly literature hampered his scholarly pursuits. Therefore, in 1949 the researcher’s old colleagues and former students persuaded him to leave Germany for the US, where he obtained the post of guest lecturer of Slavic studies at Harvard University.

At Harvard, as everywhere else before, Chyzhevsky promoted Slavic studies as well as the translation and publication of Ukrainian and Russian literary works. In the US he wrote the following works: An Essay on the Comparative History of Slavic Literature, The Unknown Gogol, The Labyrinth of Komensky’s World, etc. However, Chyzhevsky, a true European, felt ill at ease in North America, and considered American Slavic studies “dilettantish” and “superficial.” He was also homesick for Germany. In a letter to Thomas Mann he wrote: “Nowhere else could I feel at home better than in Germany. Nowhere else could I participate in building a new Europe so fully as in Germany.” Nor did the scholar find a common language with Ukrainian and Russian emigres. Oddly enough, Chyzhevsky’s poor command of the English language also hindered his assimilation into the university faculty. After 2 or 3 years he began to dream of returning to his “native Germany.” Thanks to the efforts of his colleagues and grateful pupils, Germany widely celebrated Chyzhevsky’s 60th birthday in 1954 and a collection of his works was published there.

Ukrainian circles took a dim view of the researcher’s close contacts with the Russian diaspora, reproaching him for “insufficient patriotism.” In his turn, Chyzhevsky believed that cultural ties between people and nations were more important than political ones. He thus did his best to support and develop these ties, no matter what the ethnicity of the people with whom he was in contact.

At the same time, Soviet and East German Slavists unleashed a propaganda campaign against the researcher, accusing him of Ukrainian nationalism, and condemning or ignoring his works. Soviet academia simply ignored Prof. Chyzhevsky as a scholar. Not only did the Ukrainian scholar not hide his attitude to the Soviet system, he was not against staging the odd public scandal. Once, when Chyzhevsky rose to deliver a lecture at an international scholarly conference, he said he could not speak in the presence of scholars from the Soviet Union, declaring that they had disgraced scholarship. By sheer coincidence, this took place in Prague one week before Soviet tanks rolled into the city (1968). The conference participants began to consider the Ukrainian scholar a clairvoyant of sorts.

Yet, in spite of everything, Chyzhevsky never stopped working: he published the still-relevant History of Ukrainian Literature (from the Christianization of Rus’ to the 19th Century), The Unknown Gogol, and contributed numerous articles to the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, and other works.

FINAL YEARS

In 1957 Chyzhevsky returned to Germany, full of creative verve and plans, perhaps forgetting that he was over 60 and had no prospects for obtaining a decent pension in that country. He still continued to work, nurture young researchers, and popularize Slavic studies in the Western world. The scholar won wide acclaim for his work: a jubilee collection Orbis Scriptu was published in honor of his 70th birthday in 1964 with contributions from liberal arts researchers from all over the world (minus his Soviet colleagues, of course). Chyzhevsky was elected chairman of the German League of Slavic Teachers and full member of the Heidelberg and Croatian Academies of Sciences.

Assessing his scholastic legacy in connection with the jubilee, Chyzhevsky wrote, “Looking back on what I have done, I must say it is the Czechs who will have the most enduring interest in my opuses: I mean, first of all, the discovery of Comenius’s manuscripts and the ensuing study of Church Slavonic literature in the Czech lands and Czech baroque literature. With certain exceptions, my Ukrainian compatriots do not understand what I have been doing, so last year I considered it necessary to withdraw from several Ukrainian cultural organizations. As to my research on Russian and Slovak poets and thinkers, they are at best being ignored in the two countries because they are infinitely removed from Marxist ideology.” This was a very bitter confession for a person who had devoted his entire life to scholarship.

Dmytro Chyzhevsky died in 1977 and was buried in a Heidelberg cemetery, amidst old elms and birch trees. His pupil Assya Humesky, Professor of Slavic Studies at the University of Michigan, wrote: “Dmytro Chyzhevsky died alone. Those who ministered to him on his deathbed were not his kinfolk; still, they were by no means strangers: friends, disciples, and former colleagues. A sad end, but everyone has his own destiny.”

DISCIPLES, COLLEAGUES, AND FRIENDS ON DMYTRO CHYZHEVSKY

“With Chyzhevsky’s death the world has lost one of the most prominent Slavists of our time and the last representative of the liberal intelligentsia of the former Russian Empire. Chyzhevsky was by far the last professor in Europe, who will long remain the subject of legends, stories, and anecdotes. He showed utter contempt for meanness and mediocrity, which he expressed in the formula ‘There is not a single thought in his head!’ He was the ‘scourge of God’ for such students. Nor did he give quarter to his colleagues. For example, he interrupted a speaker at a scholarly congress with the objection, ‘Does the gentleman consider us Hottentots to come here and tell us these kinds of stupidities?!’

“In the context — today the historical context — of tsarist Russia, Chyzhevsky was a Ukrainian and opposed himself to Great Russians. He emphasized this even when he was working in America, at Harvard. Never did he forget to underline that ancient Rus’ literature was in fact Kyivan, i.e., Ukrainian, literature.” (Andrzej de Vincenz, Polish-French scholar and professor of Heidelberg University).

“There was always something grotesque in his behavior, but he certainly was a great sage. Endowed with an excellent memory, he claimed that he was unable to forget anything. He used to type all his works into clean copy, with all the notes and bibliography. He knew everything and was the kind of academic who knows everything that others do not know. Chyzhevsky was the only person I know who could talk of ‘the year 37,’ meaning not 1937 or even 1837 but 1037, in which he felt as much at home as in the current year. He studied Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian baroque literature, as well as 19th-century Russian literature, especially Gogol. Chyzhevsky wrote nothing at all about what he considered a nonexistent phenomenon, something that was outside the bounds of literature, for example, Socialist Realism. He maintained that Russia had no literature at all: there were just Russian writers there. He had a lot of Polish friends and sometimes joked that the Czyzewskys once belonged to the old Polish nobility (szlachta), which was much more exalted than the Russian dvoriane.” (Hans-Georg Gadamer, German scholar, a longtime friend of Chyzhevsky’s).

Dmytro Chyzhevsky once wrote, “My life’s journey brought me from Russia to Poland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Holland, Sweden, etc., and I could see everywhere that the narrow limits within which history had put the life of these peoples had an adverse economic and cultural effect on these countries and peoples. This will further slow down their development, unless the narrow limits are removed by all means, without violating, however, the natural rights of these large and small peoples.”

In this article the author made use of the Proceedings of the Scholarly Seminar “Dmytro Chyzhevsky and Worldwide Slavic Studies,” Drohobych, Kolo Publishers, Ed. by Roman Mnykh and Yevhen Pshenychny (Ivan Franko State University, Drohobych, and the Jan Amos Komensky German Society)