The Slaboshpytskys: between a camera and a book

Relations between fathers and sons are always far from being easy, but when both a father and a son are strong, realized personalities, this is a ready drama.

But when we were interviewing film director Myroslav Slaboshpytsky and his father, a well-known prose author, literary critic, publisher Mykhailo Slaboshpytsky, our purpose was not to reveal some or other plot in their relations – we simply wanted to understand on what soil the talent is growing.

It is for you to decide whether we succeeded.

MYROSLAV SLABOSHPYTSKY: “A MOMENT OF SYMBOLIC PATRICIDE COMES FOR EVERY ARTIST”

Myroslav, what was the atmosphere you were growing up in?

“I will try to recall. My parents divorced when I was 12. However, they did not especially stress me out because they both of them were working. So, cinema was the brightest impression of my childhood. I went to movie theaters, such as Vatutin Cinema, Kyiv, Prohres, Komunar – currently it is called Kinopanorama. My parents were working and gave me good money for breakfasts. That was enough for two or three films a day, and it did not matter what the production was, American films or any other. My affair with cinema started in childhood. I did not tell my parents about that.”

Hasn’t the fact that your father is a writer influenced you in any way?

“Yes, he had many books. At the bookstore Siaivo there was a room only for the members of the Union of Writers, and it was there that my father bought books that were in short supply. At home there was a huge pile of books. If we sold them we could buy a Volga. However, I learnt to rebel back in my childhood, so when he told me to read some book, I knew I would never read it. I tried, but that was simply a torture. Therefore I don’t know anything from Fenimore Cooper. No, of course, I read books. The American detective books, for example, those by Rex Stout were the best. You could not find them anywhere. I had the Ukrainian translation of The Hobbit published by Veselka in 1985. This book got me so impressed that I almost went crazy, I was thinking, ‘Is it possible?’”

Everything is clear with the books, what about writers?

“I spent a lot of time in the House of Writers in Irpin: we were living there in summer, namely among litterateurs. I was impressed by the fact that they were experts on agrarian things: they knew what ninety-knot was and other plants, because most of them came from villages. Of course, my friends were first and foremost the friends of my father. I was friends with Viktor Blyznets, the author of the wonderful book The Land of Fireflies; he gave me toy cars and chocolates. I also liked very much Dmytro Herasymchuk, a prose author from Bukovyna: unfortunately, he deceased long ago. I recognized Ivan Drach because of his bald head which he had in spite of his young age. That was the place where I tried crawfish for the first time, because writer Borys Komar boiled it regularly. It was always funny to see how writers were playing cards, a karbovanets for a game. It was namely in the House of Writers in the First Building that I borrowed the idea of playing for money. Another amazing thing was billiards. I could not play it often, it was the holy of holies. After all, it was there that I learned to play billiards, although I have lost the skills by now.”

What have you borrowed from the older friends?

“Some mimetic things. As a child I was trying to imitate my father in the following way: I sat down at a typing-machine, took an unlit cigarette and pretended that I was writing. I stole my first cigarettes from my father. I was lucky that he smoked BT, not Prima. That was a kind of psychoanalytical story. No doubt, now, at the age of 40, I can recognize the features of my parents in myself – both positive and the ones I did not like. A person at the age of 15-16 thinks that all adults are idiots. I think I was not an exception in this sense. But I argue with him in my mind even now.”

Did you have a hiding place?

“Movie theaters were the main hiding place for me, later – a bad street company, later – video salons. I liked to watch television, too. There is a mistaken judgment, because of which my friends don’t let their children watch TV, because their parents did not let them watch it. But a whole generation of directors grew up on television, for example, Scorsese whose mom left him at the TV set for the whole day when he was a child.”

When did you understand that your childhood was over?

“At the age of 15 I came to Kochnev’s theater studio, because I dreamt to become a film director – an ungrounded dream at that time. So, I came there and in a month I became indifferent about anything else, the school and the family. At the studio there was a real life and real friends. But you cannot say the same about the money. Incidentally, my father should be paid his due – be it not for his funding of the film Diagnosis, my life would have taken a different course, I am sure. That was his good will. With this film I went to Berlin, took a different look at my life, and finally we got to the point where we are now talking with you.”

What is your parents’ attitude to your work?

“It makes my father proud, especially The Flame, he reads all publications about me. He has recently become an Internet user. Previously he used to subscribe to newspapers, call me and tell me everything they wrote about me. He is, by the way, an active reader of Den. Mom saw more what was behind my work and supported me, too. Now I have a normal profession. As a matter of fact, being a director, a person can stay without any concrete work till the age of 40, and the family gives up on you.”

Does an artist need a home? Is a conflict with his family more productive?

“I know people who were overwhelmed in their childhood by their outstanding and successful parents. My father was different. He comes from a village, he has achieved what he had wanted, making a huge step forward. I love my parents, but I think every artist faces a point of symbolical patricide at some point of time. And the next generation will sweep me away from the face of the earth, because something precious can be born only in a debate with authorities or through rejecting them.”

MYKHAILO SLABOSHPYTSKY: “It’s very good that I stopped dreaming of the Pestalozzi laurels”

Where you a liberal father?

“Remembering how I was raised in the village, I decided never to beat my children. Still I have tried to change my son’s choice somehow, even break him. This is a widespread parental desire – they want to have not what they have in their child, but what they want him to have. So, I was trying to make an athlete of him, because I myself had a category in gymnastics, played for the Ukrainian national student football team. I wanted him to follow in my footsteps. And in such a way I was torturing him.”

What was the surrounding?

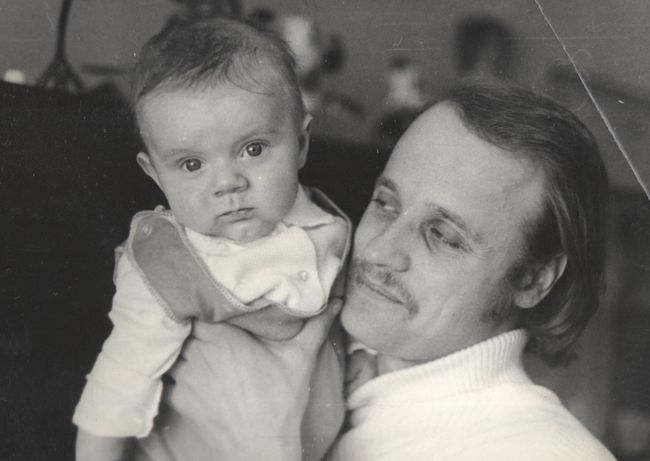

“It was very nourishing. In a recent interview he said: when he visited his friends, he noticed that something was strange with their places. Later he understood: they didn’t have any books. He was growing up surrounded by books and litterateurs. I was friends with Volodymyr Kiseliov, the father of poet Leonid Kiseliov, Volodymyr Zatonsky, Anatolii Shevchenko – unfortunately few people remember him these days, but he was a special person for our generation: he was a friend of Viktor Nekrasov and Hryhir Tiutiunnyk, a walking conscience – we don’t have people like him these days. We frequently gathered at our place and Myroslav, who was four or five at that time, was crawling on our backs, heads, hanged about among the adults. He had full ears of our conversations. He knew who was who in literature. Since the age of five he used the words like ‘graphomaniac.’ We spent every summer in Irpin, in the House of Writers. I remember him looking up at Zahrebelny, because the latter was very tall, a real giraffe. One day Tiutiunnyk stayed for a night with us. Myroslav woke him up, splashed water at him. And the writer fondled him, he liked him very much. Hryhir was on the whole a very kind man, he became mad only when he was drunk or when he was reviewing his talentless colleagues. But he liked children like puppies. There was also a summer in Irpin when Ivan Mykolaichuk was staying there. He and Drach were writing a screenplay. It was easy to love Ivan: he was looking effective in a black wide-brimmed hat, like a patrician among simple writers. And Myroslav was always following him with open mouth. He knew that Mykolaichuk was an actor and a film director and took a great interest in him. I think such episodes sent him signals into the future. That was how he was developing with our books, plus he had the environment. We were lucky to know such worthy people.”

You haven’t said anything about his school.

“He was not an excellent student. Some subjects did not come easy for him, because he took no interest in them. But still he was better developed than his peers. He saw where I hid the books I didn’t want him to read at the age he was, and he read namely them. I checked his school diary maybe once in a month. Teachers wrote many recommendations for his parents to pay attention to his misdeeds. In a word, he was a lively boy, not driven into Procrustean bed of a student with perfect behavior.”

But there must have been a temptation to press him with authority.

“Of course. Like any parent. I worked as a literary critic, so I was a mentor-preacher. But Myroslav got bored when I started to moralize. Now he is tougher, but at that time he seemed to be made of clay, and I was surprised to see that he did not stuck to me. But soon I discovered with pleasure that he had a penetrating mind. He said, ‘I hate this Ukrainian literature we are being taught at school.’ All these Institute Students, Lazy Bones. I wrote from his voice the article for which I was reproached. I wrote that Ukrainian literature that was taught at school was harmful, because it is depressive. I saw: he took Pluzhnyk’s book, he was reading Stus – cool! So, he was drawn to really interesting texts – he was a clever child, but his intellect was heretical, not the one fostered at school. Complete independence, autonomy, he had his own opinion about everything. A friend of mine came to my place, and Myroslav, a school student back then, made a verdict, ‘He is a graphomaniac, an empty spot.’ He was a polite kid, but when he did not like something, he seemed to be almost breathing fire. One day I was called to the school headmaster: Myroslav had a conflict with his teacher of Ukrainian language and literature, he got only Cs. I had a look at the exercise book and saw that the teacher made mistakes when she was correcting him. She didn’t know the language, unlike Myroslav. I showed it to the headmaster. As a result, she was dismissed.”

That was not the last conflict, wasn’t it?

“He was almost expelled from school when he was in the 11th form. That was the time of student Revolution on Granite, so he and his friends went on a strike at school. He and several more students were expelled. I had to put efforts, so that they took him back and he could get a school-leaving certificate.”

When did cinema begin?

“Myroslav was lacking money all the time. I wondered why? He started to smoke early, maybe he was spending his money on cigarettes? It was cinema, as it turned out. He watched all films at the Kyiv Movie Theater. Sometimes four or five films a day. I came home and got angry because the son was not at home at 9 p.m. And when he was at the sixth form, he got to the Kolo Theater to Oleksandr Kochnev. I went there, met Kochnev, I liked him because he was very intelligent, and I saw that he was investing much in Myroslav, saw talent in him, and as a result he made a very positive impact on his creative work. Later my son and I had a terrible fight.”

What happened?

“I didn’t want him to enter the cinema department of the Karpenko-Kary Institute. The ruin began then. I told him that he would be starving, that cinema is an expensive toy. I recommended him to enter a law department. (Its dean was a friend of mine.) I told him that he could get the profession of a lawyer and if he did not like it, he would be able to study for a film director as his second profession. We had a fight. His mother supported him, and I gave up. The dean of the cinema department was Vasyl Tsvirkunov, a husband of Lina Kostenko who knew Myroslav and liked him a lot, so I knew they would not plough him at the exam.”

When did you understand that his childhood was over?

“When he became a student. I understood that he was a different person. Apparently, he himself felt that it was a halfway to his self-realization. He had not become himself, but he was moving towards himself. At that time I understood that there was no way back, but I also revealed the fact that he was a whole thing in himself, a system absolutely closed from others. He mentioned the teachers only my nicknames. I didn’t know who his friends were and that he had sold his camera.”

What is the story?

“I went many times on trips to Canada. Once I was presented there with a nice Japanese camera. I gave it to Myroslav, because I am not on friendly terms with technique. Recently he admitted that I became his investor by doing this. He had to do a diploma film, and there was the time of total poverty. He sold the camera, went for this money to Lviv and shot his diploma film. By the way, his current success is gratifying for me because Myroslav had had a terribly difficult period, when he could not find a place to take hold. It seemed that he had no point of support. He is a fair and truthful man, he can flush with anger, but he is not an evil person. I helped him to get employed at the charity Chernobyl foundation at Moskovsky District Council. He worked there for three days, quit the job and said: ‘I cannot work there. They are stealing, rascals.’ He had conflicts at TV channels. It was 1993, he had no job or expectations. The situation remained the same for six or seven years, he had complexes, he repeated that he was a loser, and that his father was ashamed of him. He went to Petersburg, found a job there, but I tried to persuade him to come back home.”

Did you succeed?

“He came from Petersburg with a screenplay for a short film with the title Diagnosis. Together we were thinking on where to find 120,000 hryvnias. We used the money that remained from my Shevchenko Prize, sold several books, and also got some funding from the Darnytsia pharmaceutical firm. I saw the film and was terrified, ‘I like the film. But where’s patriotic realism? They will tear you down. It is too cruel.’ Such film, which was shot in a ‘guerilla’ way, suddenly went to Berlinale. That was how everything began. That was how he returned home.”

Have you had any problems with understanding of the cinema he is making?

“When The Tribe was released, I said, ‘Myroslav, all adepts of Ukrainian poetic cinema will be against you.’ Even my assistant at Babylon cinema magazine Larysa Briukhovetska was among them. I think we have been traumatized by the post-colonial situation. The entire sphere of art and literature must work on developing or defending the nation. This is not France or Italy with free development and the struggle of schools. We have been crippled aesthetically, we are crushed, underdeveloped. In a word, this is post-colonial aesthetic narrowness. Imagine, if a Ukrainian Jean Genet emerges? What will be left of him? The society is not mature enough. But I did not feel any aesthetic rejection for his films, maybe fear that he was making his creative path complicated.”

But Myroslav is in a great conflict with his colleagues.

“I will repeat myself, his maximalism and sharpness have no touch of malignancy. Another thing is his rebellion against those workers of cinema. I know my milieu of writers – it is specific in this sense as well, mildly speaking. There are no sentiments, when people treat you like that. You did not step on anyone’s foot, but people wage a corporative war against you till destruction. Myroslav has a different nature, but his is blocking someone out of the sun. Some people think he has stolen success from them. Envy is one of the main human feelings.”

Is home important for an artist?

“The most important thing is what happens to his soul. There is artistic mind and there is a folkways mind. I think a person needs to feel that he is not alone. Myroslav was lucky that he had wonderful grandfathers and a grandmother on his mother’s side. They loved him very much.”