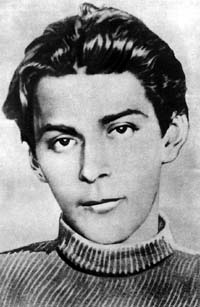

Pavlo Tychyna: drama of the vanquished?

CLARINETS OF TENDERNESS

Young Tychyna wrote in the unique language of his heart, unparalleled in the world. God bestowed on him a wonderful ability to hear the Music of Cosmic Infinity and quiet, unknown to others, voices of Nature which he interpreted as a single whole, never dividing them into animate and inanimate (when he says hello to a chamomile and the latter says hello in reply, this is by no means infantilism but, rather, the highest manifestation of the wisdom humanity will reach about two centuries later). “Grain seeds keep falling from deep Eternity into my heart,” thus the young Pavlo wrote himself. And more, “I’m putting up a sail in my heart, for in my heart is sadness...”

The outstanding Ukrainian writer, poet, and philosopher Vasyl Barka, noting Tychyna’s strikingly figurative thinking and his crystal clear (but not simple!) style, uses the term clarinetism, which the poet himself used to characterize his creative work. Barka writes in his book, Peasant Orpheus, “The live water of Tychyna’s early poetry flows from the eternal song and its sincere, almost childish, faith.” The emigre poet calls his poetry “the voice of a skylark in the sun of an alien day” (he said this as long ago as 1961 on the occasion of Pavlo Tychyna’s seventieth birthday).

According to Vasyl Barka (it would be very interesting to compare the writing manners of the authors of Barka’s novel The Yellow Prince and of The Sunny Clarinets, who wrote some Dantesque-level powerful poems on the 1921 famine, for example, A rifle butt pounded on the door...), the tragedy of Tychyna’s writing and life lay in “the loss of connection with the clear blue sky of faith” and the never ending search for “a prayer for his heart” amidst the surrounding bestiality. Another comment by Barka, “Tychyna’s lyrical universe could only blossom if mysteriously connected with a millennium of the purely spiritual victory won in the times when hearts were full of kindness and the truth of life would open like flowers in spring... This why, instead of putting revolution and counterrevolution in opposition, Tychyna distinguishes between what is human and inhuman.

Yet, the cruel era of truly geological social upheavals left Ukraine’s great poet no opportunity to further follow his personal distinguishing lines. Tychyna found striking images (on the level of the best examples of world poetry) of the epoch’s inhuman spirit: “a fiery horse at night,” “a claw-eyed blackbird,” “a blackbird from the rotten depths of soul.” “My Madonna, the Immaculate Mary glorified in centuries! Only the wind blows over our deserted altars...” Such cries of the poet’s wounded heart closes the temporal and national distances and makes an impression that these lines were written precisely now, not in the terrible 1918.

THE GLINT OF STEEL

The son of an ordinary Chernihiv peasant ascended to dizzying heights of the human spirit. This revealed to him the simple and eternal truths of history: any violence is futile, especially in the guise of demagogic slogans. Tychyna could write about this in the simple terms that distinguish true poetry, “A great idea requires sacrifices. But is it a sacrifice when one beast eats another?”

The new regime had an excellent memory. And nobody would have forgiven the Poet his 1917 Anthem of Independent Free Ukraine (poem “The Golden Echo”) or the requiem for the Kruty heroes (“Thirty Ukrainian martyrs, young and bold...”). To survive, one had to compose his “Anthem of a New World.” The poet made his choice. This resulted in what was studiously hammered into the heads of Soviet schoolchildren (An Answer to Compatriots, 1922; Lenin, 1924; The Party Leads Us, 1933; The Sensation of a United Family, 1936; etc.).

The crucial question is why this poet of genius chose to laud inhuman iconoclasts. Barka skillfully pointed out the bitterness of the Creator’s invisible sufferings, “Tychyna’s chest was adorned with awards. But this caused violent ruination under the medals in his heart as well as in poetic vision... He could not afford the luxury of a neutral opposition to the official opinion either in Kharkiv or in Kyiv. The poet was forced to admit that the Soviet rain would fall only after the Central Committee had passed a resolution; he even wrote an ode to this news.”

As to why Pavlo Tychyna so tragically switched allegiances, there is a poem, hushed up for decades, which sheds lights on this problem. In 1926 the Poet appealed for help to his spiritual brother, the great Bengali, Rabindranath Tagore. Read carefully these wonderful lines, “Rabindranath, my love! Come here to Ukraine from far away Bengal, for I lose my breath, I am dying. I will show you feud among people of the same class. I will show you all the falseness and rottenness of Party creations. And fraternal teeth? And friendly oppression? A policy flexible like wax. If they were generals, we would know what to do. But the point is they are butchers from the same class...”

The terrible necessity of making a choice has existed in all times: either you, poet, will sing with us or you will be destroyed. Such contemporaries of Tychyna’s as Gumiliov, Khvyliovy, Garcia Lorca, and Mandelshtam chose to die. Our poet opted for life. Who can reproach him for that? “Tychyna’s poetry is an example of how the native faith is being stifled and the nation’s inimitable creative face is being disfigured,” Vasyl Barka quite rightly wrote. Thus we, those who live in 2002, have only one way out: to revive this “nation’s inimitable creative face” every day with painstaking effort.

DEFEATED?

The most interesting thing is that it is also not so simple with the Poet’s canonical “Stalinist” verses. Let us take the word “Bolshevized” (“...of the Bolshevized era”) from “The Party Leads.” A young researcher Vitaly Mateush quite aptly noted that this word resembles in form (in Ukrainian — Ed.) such words as “perverted,” “raped,” or “Russified.” If Party censors had known the Ukrainian language well (the poem “The Party Leads” was printed on November 21, 1933, in Pravda in the original, with no Russian translation), Tychyna would have certainly been destroyed.

And here is the comment of Lviv- based poet and Tychyna researcher Viktor Neborak, “To be a Ukrainian poet means to be hidden from the rest of the world, to be unnoticed. What is unnoticeable in Tychyna is his Ukrainian self. And what is his Leninist and Stalinist verse stands out too much. But the more noticeable things are, the sooner they bore you. Tychyna seems to have known the price of this too noticeable level of things... Non-resistance to the Leninist-Stalinist evil is Tychyna’s Christian choice. Having sacrificed his Ukrainian sunny clarinet self, he still preserved his own sunny clarinet.”

Tychyna has been forgotten as a Stalinist bard — and deservedly so. But no one will ever forget the great poet of tragic inner sufferings, who put striking words into the mouth of a young man whom his mother blesses to go and fight the enemy, “My mom! There is and was no enemy. Our only enemy is our own heart. Bless me, mom, to search for a potion to cure people of madness...”

When Pavlo Tychyna discarded the friend-foe, White-Red, and opposition-regime dichotomies and began to reflect on the eternal human and inhuman, he created eternal masterpieces of world poetry. This is where Tychyna is immortal.