Caricature as a way to keep the spirits high

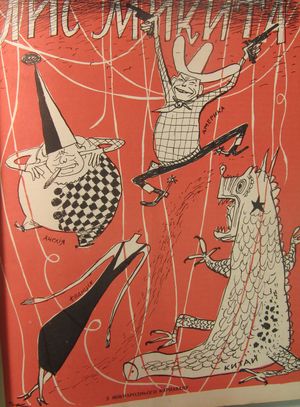

This year marks the 110th birthday and 20th death anniversaries of Edward Kozak, a cartoonist and founder of Lys Mykyta satirical magazine, a favorite read among the Ukrainian emigrants

LVIV – Numerous artists and art critics tried to register Ukrainian art’s experience on the global cultural planes. One of such artists was Edward Kozak (1902-92), a cartoonist, humorist, artist, icon painter, writer, editor, and publisher. “I am as diverse as my art: Edward Kozak, Eko, Mamai, Mike Chichka, or Chap-Chalapcha,” he would say about himself.

Kozak’s artistic heritage is an extraordinary phenomenon. He was capable to psychologically adapt and realize himself in contemporary artistic concepts in the multicultural environments of Lviv, Krakow, Berlin, and New York City.

Kozak was born into a farmer’s family near Lviv. Despite his German descent, he clearly identified himself as Ukrainian ever since childhood. He was educated at the Stryi Gymnasium, later at Oleksa Novakivsky Lviv School of Arts and at art schools of Vienna and Lublin.

Although nominally Kozak belonged to the so-called “Novakivtsi” group [the followers of Oleksa Novakivsky. – Ed.], he eventually overcame the school’s influence, found his own expressive means, and pursued an individual artistic career. He revered his teachers and held the artistic quests of his colleagues in high respect, but he was always loyal to the latest trends in art, and to exciting, unknown cultural horizons. He preferred to be influenced by Paris and Europe, than Russian realism, old or new. Kozak saw the manifestation of Ukrainian character in art not as a denial of European artistic achievements, but as an interpretation of these achievements and adding a distinctly Ukrainian coloring to them.

The artist would always emphasize, “Artists should remember that Western artistic culture grew through overlapping of various epochs and achievements of many European nations… many of which are part of Ukrainian artistic culture.”

As early as in the 1930s in Lviv Kozak published his cartoons in humor and satire magazines Zyz (Squint) (1926-33) and Komar (Mosquito), which he edited, illustrated all Ivan Tyktor’s publications (1933-39), designed magazine covers, sketched and painted in oils, and participated in the ANUM (the Association of Independent Ukrainian Artists) exhibits and in the city’s social life.

Here are some of Eko’s reminiscences of interwar Lviv bohemian life: “We were experiencing a kind of Galician Renaissance… We would sometimes have gatherings which we dubbed Thursday Parties (or Fairs, in my interpretations). The place was always the same, cafe De la Paix on the first floor of the building opposite the Mickiewicz Monument, in a spacious, light room adorned with a crystal chandelier and discreet columns… On Thursdays it was a venue for painters, poets, theater-goers, musicians, news writers, ‘Novakivtsi,’ and ‘ANUMists.’ It was the bohemia of Lviv, who had in their hands the keys to the Ukrainian Lviv.” At least, this was how it looked like before the World War II and the Soviet occupation of the city.

Later, many artists (including Kozak and his family) moved to Krakow, from where he moved to Germany in 1944. Emigration made its amendments to the painter’s life and art, but it did not stop him from being actively involved in cultural activities. He led the Ukrainian Association of Fine Artists in camps for displaced persons. It was there that Kozak started publishing his satirical magazine Lys Mykyta (Mykyta the Fox), which he will continue in America, perpetuating his name in the history of the Ukrainian caricature.

In 1951 Kozak moved to the US, namely, Detroit, Michigan. There he worked in the sphere of church art, illustrates fairy tales for television, designs books and magazines. He also continued to publish Lys Mykyta, which was a favorite read among the Ukrainian emigration. The artist also owned a publishing house of the same name, Lys Mykyta, and supported a Club of Caricature Fans in Art.

Kozak’s themes in painting and cartoons ranged from Sich Riflemen to Hutsul lands to Ukrainian countryside. His favorite topics were tragicomic portrayal of Stalinism and its atrocities, and Ukrainian artists in emigration. He always had a rational and constructive approach to events and he viewed them in the light of Christian ethic. He believed that the most important thing for him was to keep his artistic “vision” intact in the vortex of cheap routine.

Kozak reached unique logic of art: the logic of irrational in the caricature, and grotesque in the cartoon. He believed grotesque, cartoon, and caricature to be a kind of art which can only be approached via portrait. Actually, Kozak painted a lot of portraits, conversation pieces, and even tried himself as still life artist and icon painter. He was able to convey his mood in the line. A subtle sense of humor and the ability to recognize and visualize a character helped the painter to successfully render a number of various situations, silhouettes, and images.

“When I draw, I don’t know why people laugh afterwards,” Eko would say. “I try to capture character in a definite person or situation. Maybe, it is because we all are so funny.”

Kozak’s art raised the role of cartoon and caricature in arts. He proved that a cartoon is the most adequate method to render the psychological nature of an image, state, mood, or emotion. Both caricature in art and satire in literature have an educational mission, targeting people and life circumstances. He also proved that the caricaturist and the satirist in a way are commentators of the most burning problems, events, and situations.

Kozak had a good friend who shared his views, Sviatoslav Hordynsky, a renowned artist and art critic. Hordynsky emphasized that “certain elements of satire could even be spotted in our old icons, portraying the Devil on The Day of Doom.” He traced Ukrainian caricature back to the 17th century, and listed Taras Shevchenko as one of the first caricaturists of the 19th century. Among the 20th-century caricaturists he singled out Teofil Terletsky, who illustrated the German humor magazine Fliegende Blaetter (Flying Leaves) in Munich; Osyp Kurylas and Osyp Sorokhtei, who created Sich Riflemen caricatures; and caricature painters Viktor Tsymbal and Borys Kriukov, who illustrated the satirical magazine Mitla (The Broom) in Buenos Aires.

Hordynsky underlined special role of Kozak, whose cartoons where reprinted in Polish, German, English, Dutch, Italian, and American press.

Kozak had a unique vocation. Although, due to political reasons, he had to spend the most of his life in emigration, he never drifted to the periphery in art. Instead, due to his daily work, confidence, and a subtle, shrewd sense of humor he perpetuated his art in world culture. Kozak believed that in Diaspora Ukrainian society consists of small communities with the micro-climate of a “Ukrainian family,” which shaped Ukrainian presence in American multiculturalism. Artists’ main goal is to keep up the Ukrainian’s high spirits, sentiment, and cultural vigor.

Everyone knew Eko, from a toddler who grew up with Chap Chalapcha and Hryts Zozulia to adults, who mocked at Stalin and his regime through caricatures in Lys Mykyta. Kozak’s art kept a cultural balance, albeit only locally in Detroit – but his humor was admired worldwide in the Ukrainian Diaspora. Perhaps, Kozak was the only caricature artist who lived on polycontinental planes of culture.

Newspaper output №:

№25, (2012)Section

Culture