Anthology of hope

New book by writer and conductor Roman Kofman reminds: our world is a music theater

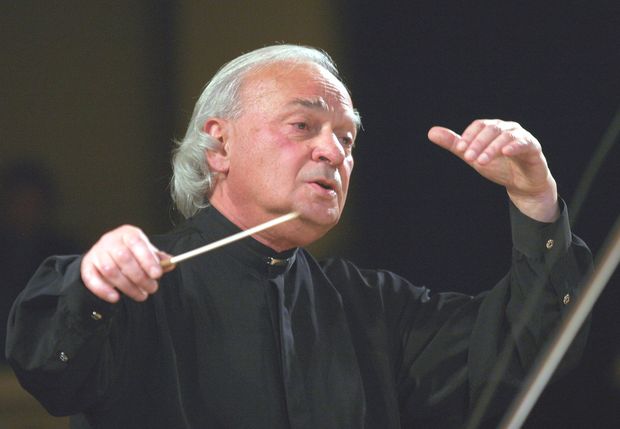

The music of this prose is beautiful, therefore it is hard to write about it: you want to quote it. Probably the book It will be always like this (publishing house Laurus, 2014) has one disadvantage – it ends. And there are many wonderful peculiarities, starting with the cover, which is pouring light, subtly outlining the profile of the maestro in the background of cosmic darkness. Clear phrasing, brilliant grotesque, pinching lyric pauses. The turn of phrase is aphoristic, airy, ironic, and trustful; it creates a music space of the text, the life where dramatic, tragic, and anecdotic episodes change one another. It is a place where both well-known personalities, such as Shostakovich, Stravinsky, Rostropovich, Virsky, Rakhlin, Bibik, Paert, Silvestrov, and even Horbachov, and so-called ordinary people, “good and different, happy and not so happy,” meet. And the gold placers of exclusive Kofman’s humor, like in the final of the preface, “At the end I will share good news with you: the reader, you can start to read the book you are holding in your hands from any chapter. This is its advantage over other works of the world literature.”

The book contains the short story written in 2004. It is called “From the chronicle of the collective farm ‘Laziness of Putin’ (formerly ‘Way of Lenin’).” It tells about the incredible adventures of the collective farm’s symphony orchestra as it is touring abroad. In the end the reader will find how the collective farm received a new title: “There were many offers, but the lack of funding was restricting the flight of imagination. We had to make huge letters of plywood, but we had no money either for plywood or carpenter. Therefore we decided to use the former letters, but put them in a different order to create a new title.” So, one day one of the characters, Khoma Lukych Aizenberg, when he went for a walk, saw that “on the square near the gates instead of usual ‘Way of Lenin’ (Put Lenina) the incomprehensible ‘Laziness of Putin’ (Len Putina) was heaping.”

The author specifies, “This story is faction from the first word till the last one. But it is actually more truthful than any protocol or documentary.”

The Day asked Roman Kofman to raise the veil over the mysteries of creative work.

Mr. Kofman, in the preface you say that you collected stamps in childhood, but after the collection found itself in a pot with soup your aunt was cooking (don’t keep albums on a shelve above the stove), you switched to “memorizing motley pictures,” generously presented by life. And your book, which one reads in one breath, is a result of this collecting.

“It was written in two breaths. Firstly, almost the whole piece – in one breath, then there was a break. Then the manuscript disappeared. The thought that ‘manuscripts don’t burn’ was consoling me, but for a long while I could not find it and was very happy when my son-in-law found it by accident. I am thankful to the employees of the publishing house Laurus: they waited for me, hurried me, encouraged me, ‘threatened’ me, and helped me a lot, in particular, with typing. I write with a pencil, like Viktor Nekrasov. I feel the pencil as something warm and dear, a thing from school, whereas the pen is already a mediator. I haven’t mastered the computer. This is a strange instrument for me.”

The book has a beautiful beginning: on a separate page there is a dedication “To my wife Iryna.” You write about the origins of the biography of Iryna Sablina, the founder of the world-renowned choir Shchedryk, in the chapters “Me, Mao Zedong, and others,” and “A Saboteur’s Daughter.”

“This year on April 29 Iryna Mykolaivna and I celebrated the 55th anniversary of our marriage, and for seven years before the wedding we were friends. Besides, on May 7 was her birthday, she was born in a good company (on the same day as Tchaikovsky and Brahms). And I made a present for her – a concert. A novel can be created based on the chapter ‘Saboteur’s daughter,’ and hopefully I will write it: the life of her parents deserves a separate book.

“Mykola Sablin, my father-in-law never told about the tortures he suffered during the investigation. He was accused of being a Japanese spy who smuggled the gold extracted in the mine where he worked to Japan and of blasting five bridges. He was saved by his childhood friend who turned out to be an NKVD investigator. He interrogated him and when the bosses came in, he terribly swore and hit him with a newspaper on the face, so that it did not hurt, but when in private they were talking and recalling their childhood. He persuaded Mykola Ivanovych to sign a confession, not to be killed. He received a maximum prison term of that time – 10 years without any right of correspondence. It seems not so bad, but in fact it was an unending imprisonment, when he received new terms because of various reasons. He was sent to prison in 1937 and was rehabilitated in 1956, and only 19 years later Mykola Ivanovych saw his wife and his daughter. He lived for almost 90 years and was the most joyful person in our family. He played the accordion, he knew well the choruses by Berezovsky and Bortniansky (in his childhood he sang in a church choir; his grandfather worked as a smith in summer, and in winter served as a chanter of the church choir in a remote village in Omsk oblast).”

Another story, which is impressive by its ethic message, is “Choir of Boys,” where the hero Gari, a.k.a Herman Perelstein (1923-98), a son of repressed parents, who was miraculously saved from death in Stalin’s camps, became an outstanding conductor in the Soviet Lithuania and created one of the best children’s choirs in the world.

“Choirmasters from the entire country came to Herman Godovich to Vilnius like to a choir Mecca, to watch his work with children. Iryna Mykolaivna went there too and said that she had a special feeling when he was conducting a rehearsal. Since that time she has been staying in touch with the head of the Omsk choir she met in Vilnius, – Herman became a moderator of communication of many people.

“He was a great master and an extraordinary personality. He moved to America in the 1980s; at that time I was working in the conservatory, and he arrived in Kyiv for several hours – to say good bye to us. He was very highly appreciated in Lithuania, and even his farewell was unprecedented: a visit to the secretary of the party who promised to fulfill any request if he would stay. Herman replied that he would go anyway. And he asked for a new piano for his choir and a carpet for the hall, so that the children did not crash knees when they were running about during the break. And his request was fulfilled. The choir created by Herman, Azuoliukas, (A young oak tree), where his name and legacy are honored, exists now like a well-known brand, all the more so Lithuania is an independent country with a positive image. Probably the piano is still standing there.”

Tens of characters, with whom you had short meetings in various countries, live on the pages of the book. A French-horn, violin, and piano player, Mr. Vogelgesang, whose surname is translated as “bird song.” An old Canadian millionaire, a great music lover, who paid for being allowed to perform at rehearsals. Orchestra administrator Semenych, who is sure that the life of a performer would be wonderful, be it not for rehearsals and concerts. And, of course, uncle Vasyl and Mr. Bradley.

“These are real names of the workers of the stage, ours and American. During the tour of the Ensemble of Folk Dance of Ukraine in America, which lasted for three months, the so-called accompanying persons explained to Pavlo Virsky that the conductors, Ihor Ivashchenko and I, should conduct one section of the concert each. Because if one of us conducts the whole concert, another one may meanwhile go for a walk, talk with the people he should not talk, behave like he should not behave.

“I usually conducted the second part, and during the first one I was doing different things: stood near the barrier at the orchestra pit, sat in the hall, went out of the building and wandered near the theater, which was not welcomed by the accompanying persons. Behind the curtains I watched many times uncle Vasyl and Mr. Bradley sitting on wooden boxes for inventory and talking. Uncle Vasyl didn’t know any English word except for money, and Bradley – any Russian word except for sputnik. I can still see this picture: Mr. Bradley is telling something for a long time, and Vasyl is nodding. When Bradley stops, uncle Vasyl announces: ‘So, that’s what I’m saying’ and starts to tell his story. They were talking, not knowing the language of the interlocutor, and understood one another on the level, which is out of bounds for the most qualified linguists. ‘He’s a very clever man,’ uncle Vasyl told me about Mr. Bradley.”

A fantastic story happened in Chernivtsi, when during Wolf Messing’s performance you offered to guard him, so that he did not see where the comb would be hidden. Magic qualities are ascribed to the profession of a conductor not without a reason. Did Messing told you about that?

“Yes, I saw him working. A magician? Most likely, Messing felt the impulses: he was holding the hand of the woman who hid the comb, and not simply was he going along the aisle, but tried to turn at every row, and felt from her reaction when the turn was wrong. Who could give him a hint? He had an assistant, but there were no micro hearing devices at that time.

“On that evening he was nervous and even gloomy. I understand the behavior of a person on the stage and I cannot say that his energy was positive; I thought he could not wait till the concert would end. But we had time to talk, and he asked, ‘What is your occupation?’ – ‘I’m a conductor.’ – ‘We are doing one and the same thing.’ I agreed with the famous magician, but noted that I would not find a hidden comb. Because it is hard for me to find mine in the morning!”

The book includes two chapters about Beethoven. It is known that owing to you the Bonn symphony orchestra you have conducted for five years was named after Beethoven.

“I wrote the text ‘Playing Beethoven’ for the German newspaper Bonner General-Anzeiger when I was working in Bonn and received a thankful letter from its editor-in-chief. But he noted that my opinion differs from the view on Beethoven of the majority of Germans. The thing is that there is a popular opinion in Germany that he was a rebel and revolutionary, which is considered to be his main peculiar feature. But for me he is above all an outstanding lyricist, and I am writing about this. Yes, Beethoven is a revolutionary in the sense that he broke many music rules. Not a social, but music revolutionary. But every outstanding composer broke many things that had existed before him, and this is the essence of innovation and greatness of a musician, performer, and artist.”

You are the chief conductor of two ensembles, the Academic Symphony Orchestra of the National Philharmonic Society of Ukraine and Kyiv Chamber Orchestra. This music season went amidst intense political situation in the country: part of the concerts were cancelled or postponed, but the team of the philharmonic society, being in the epicenter of the dramatic events, strived to support people with high art, and all your performances enjoyed full houses. Of course, Kyivites won’t forget your concert in commemoration of the killed heroes of Maidan “Heavenly Sotnia” which took place on February 26 and sounded like a prayer. On the disturbed winter when the philharmonic society did not work at all, the first concert after the break was the concert opening your project “All Symphonies by Tchaikovsky. In commemoration of Natan Rakhlin.” And the finishing concert of the project will close the philharmonic season. Do you have any plans for fall?

“During our concert four numerated symphonies by Tchaikovsky were performed, the Manfred Symphony will be performed on June 24. Byron’s Manfred is a romantic hero, who if not Tchaikovsky had to immerse into this sphere? Tchaikovsky was a wonderful formalist, a professor of composition. And his most ecstatic and emotional content was put into perfectly checked form.

“In autumn, on November 19, my concert with the choir Shchedryk, the first performer of Gia Kancheli’s Angels of Sadness for violin and cello, which perform the solo, and children’s choir will take place. This work was performed for the first time by Shchedryk, Gidon Kremer and Giedre Dirvanauskaite in Germany, at an international cello festival in Kronberg and in Berlin. On October 7, 2013, the day when Anna Politkovskaya was killed, Gidon Kremer wants to perform Angels of Sadness in Kyiv – in the choir’s home city – and in Georgia. November 19 is the only day he can come to Kyiv.”

Your words resonate with your short story “Plato’s Banquet.” I will explain for the readers: Gidon Kremer wanted to perform in Kyiv Bernstein’s Serenade based on Plato’s Symposium only with you, although you are not in the staff of the philharmonic society. And he could come only on a certain day and you, fortunately, were able to come from Kryvy Rih, where the festive concert with the participation of Virsky Ensemble dedicated to blowing in the blast furnace No. 9 took place. You write, “We gave a concert with Gidon Kremer: since that time we for many decades never lose an opportunity to perform together.” Your book gives hope, in particular, with its code name.

“Hope emerges if your attitude to life is right. This title emerged at the last moment – this is a quotation from the last part. Musicians and composers came to our house in Druzhby Narodiv Boulevard, where we have lived for 29 years. Gidon was our most frequent guest, Arvo Paert – a rarer one, it seemed unbelievable to see this person at home. Like Alfred Schnittke. We performed then his Concerto grosso for two violins, harpsichord, and Schnittke performed a piano part in my orchestra. He came to my place several times. Schnittke was an embodiment of intelligentsia in the broadest meaning of the word. An incredibly educated person, very taciturn, modest, and extremely elegant. His essence was in modesty and elegance. He never complained about suppression, underestimation, or hushing. His first ‘honorary’ title was the laureate of Krupskaya Prize for the music to cartoons – he received it when all of his colleagues were already people’s artists and winners of all kind of prizes. Nonetheless, his name at that time was widely known in the world.

“Let’s return to the flat in Druzhby Narodiv Boulevard. ‘Tetiana Hnidenko is playing in the children’s room, Gidon Kremer – in the bedroom, Schnittke and Paert were talking about eternal things in the living room. Kitchen is the place where everyone meets. We talked about all kinds of things, except for one: nobody described the mood we all had. Now I know what it was like: we were feeling good, like it will always be like that, we are young, we will always be living in expectation of tomorrow’s concert, and it will last forever.’”

Newspaper output №:

№43, (2014)Section

Culture