About the genocide

There were diplomats who reported the truth

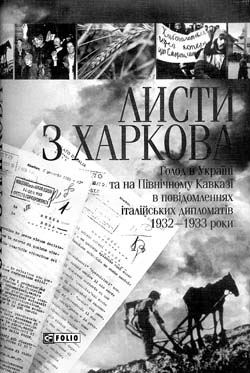

The Folio Publishing House has published a book of reports by Italian diplomats about the famine that took place in Ukraine and the Northern Caucasus, entitled Letters from Kharkiv: The Famine in Ukraine and the Northern Caucasus in the Reports of Italian Diplomats in 1932-1933.

In both “impartial” scholarly discussions and implacable polemics among opponents who are separated by invisible (at times obvious) political barricades, the quickest way to the truth and the most efficient weapon is the use of authentic documents. This new book about the Holodomor of 1932-33 is a kind of publication whose content can (and must) raise to a new level the arguments that are wielded in discussions of the range of problems connected to this catastrophe, its background, hidden motives, and direct and remote consequences. From today it may be asserted that the materials presented in this book cannot be overlooked by any diligent historian studying this terrible tragedy of the Ukrainian people.

Before I proceed to an analysis of the book’s contents, a few introductory remarks are in order. The authors of the reports to Rome that are featured in Letters from Kharkiv were experienced Italian diplomats, who were representing their state’s interests in the USSR in the early 1930s. I am speaking first and foremost about Sergio Gradenigo (1886- 1966), who was the consul in Kharkiv (and from 1934 — in Kyiv), as well as Vittorio Cerutti (1881-1961), and Bernardo Attolico (1880— 1942), Ambassadors of the Kingdom of Italy to Moscow in those years. Despite the fact that these people represented Mussolini’s fascist government, they were sincerely eager to tell the truth in their reports about the people’s boundless sufferings. The book’s compiler and author of the introductory article, Professor Andrea Graziosi, who teaches in Rome, rightly notes that “although it is somewhat paradoxical, one can consider the book Letters from Kharkiv — with their supply of human sympathy and descriptions of the ‘suffering and persecuted’ masses and their merciless prison wardens, the representatives of a cruel state and a cruel dictator — as belonging to a larger extent to the traditional culture of the European left wing of the 19th century than to the culture of such a regime as fascism.”

I will return to Graziosi’s introductory article, as it is difficult to fully understand Letters from Kharkiv without it. Now, I will introduce as briefly as possible (this is not easy because I would like to recapitulate the content of all the letters) extracts from the diplomatic letters of Gradenigo, Attolico, and Cerutti, which are the most impressive, relevant, and “necessary” for contemporary discussions, with special attention to Gradenigo, who was working in Kharkiv and thus aware of the situation in Ukraine.

In Gradenigo’s letter to Rome, dated May 19, 1932 (the most terrible months of the Holodomor were still ahead), the diplomat gives the following report: “The lines of people (in the Kharkiv streets — I. S.) who are waiting for bread to be distributed have grown endless. One can see them standing along the sidewalk of the street that is 300-400 meters long, with the shop where the bread is given out located on a parallel street, on the other side of the block. People come with chairs and books to read. Yesterday evening the distribution of bread began at 6 p.m., and I noticed the line along Pushkinska Street already at 9 a.m. The street beggars do not want to take money any more, because even with money they cannot buy bread, therefore they ask for bread.”

In order to understand the content of the letters, one should take into account the fact that neither Gradenigo nor other diplomats had access to starving Ukrainian villages. Therefore, to a certain extent the tragedy of the Holodomor is presented in the documents of a diplomat with “a Kharkiv-centric” position: Gradenigo saw the food difficulties in the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, and he wrote about this. But there is no doubt that the Italian was also not indifferent to the terror by famine (not food difficulties) that the Ukrainian peasants were suffering. So as not to horrify the reader, let me introduce a small (and not the most impressive) extract from Gradenigo’s letter dated May 31, 1933. “One afternoon I was walking along Pushkinska Street to the center of Kharkiv. It was raining. I saw three homeless people who were pretending to fight. One of them was pushed and he fell onto a woman carrying a pot of borshch wrapped in a kerchief. The pot fell and was broken. The culprit escaped, while the other two used their hands to scoop up the soup from the mud and swallowed it. They put a bit of soup into a hat for their companion.”

I will not quote from Gradenigo’s reports where he writes about the corpses of peasants who had starved to death (hundreds of them were collected in Kharkiv on the roads in that terrible year of 1933), about activists-”collectivists” who were murdered by peasants (further proof that our people were not meek lambs even in those times and were resisting), about the protests and the fierce infighting in the CP(B)U, and about the destruction of the Ukrainian national elite. Those who are interested can find all this in the book. Instead, I will focus on Gradenigo’s general contemplations on the causes of the tragedy.

“By means of merciless confiscations (concerning which I have reported many times),” the consul writes, “Moscow’s government organized not simply a famine, because this is saying little, but the absolute lack of any means of subsistence in the Ukrainian countryside, the Kuban, and the Middle Volga. I can determine three reasons dictating such a policy: 1) the peasantry’s passive resistance to the collective economy; 2) the conviction that it will never be possible to reduce this ‘ethnographic material’ (he is referring to the Ukrainian peasantry, but actually to the entire nation. — I. S.) to that form that radical communist doctrine wants it to acquire; 3) the more or less recognized necessity or preference for the denationalization of regions where either Ukrainian or German self-awareness is awakening, which carries the threat of possible political complications in the future, therefore for the sake of the empire’s integrity it would be better if the Russian population inhabited at least the majority of these lands. The third view is aimed, beyond a doubt, at the liquidation of the Ukrainian problem within several months by sacrificing 10 or 15 million people. And this number should not strike you as exaggerated. I think it will be reached and surpassed.”

Finally, I will say a few words about the analysis of the problems of the Holodomor, which is contained in Graziosi’s lengthy introduction to Letters from Kharkiv. This prominent Italian historian emphasizes that “Ukraine needs to fully regain its history and only the Holodomor can be the starting point. I hope that as a result of the publication of these ‘Letters,’ which were sent many years ago to a government that did not want to listen to them, Ukrainian society with all its components will build, on the foundation of truth, balance, and fairness, such a ‘memory’ that will enable it to heal old wounds and make its way to a better future.”

In Graziosi’s opinion, “the events that took place between the end of 1932 and the summer of 1933 allow the reader to reach the following conclusions. First, Stalin and the regime that he controlled and subordinated to his will — of course, not Russia or the Russians, who themselves were suffering from hunger, although to a lesser degree — within the framework of the offensive that was aimed at overcoming the peasants’ resistance, were deliberately carrying out an anti-Ukrainian policy aimed at mass annihilation. This resulted in genocide, the physical and psychological scars of which are evident to this day.

Second, this genocide was caused by the famine, which initially was not created deliberately with this goal, but later, having emerged as an undesirable (I. S.) outcome of the regime’s policy, was deliberately used for this purpose.

Third, the genocide was unfolding within the context created by Stalin’s decision to punish by starvation and terror certain national and social-ethnic groups who were considered to be either real or potential threats. As all the qualitative indices signify, out of all the above-mentioned causes, the punishment by starvation and terror reached its peak in Ukraine, where it turned into a qualitatively different phenomenon.

Fourth, in this perspective, the link between the Holodomor and other tragic kinds of punishments and repressions in 1932-33 is somewhat reminiscent of the already mentioned connection between the Nazi repressions and the Holocaust. However, the Holodomor was very different from the Holocaust. It was not aimed at destroying the entire Ukrainian nation, nor was it based on the direct destruction of victims (I. S.). It was determined and motivated by theoretical and political, not ethnic or racial grounds, and this different motivation is at least partially based on the first two.”

This book and the theses advanced in Prof. Graziosi’s foreword are not the final word and truth but a stimulus for a further search of this truth. But it should be underlined once more: from now on without a perfect knowledge of Letters from Kharkiv any talk about the tragedy of the Holodomor of 1932-33 will have neither content nor sense.